In the late 1950s in Fiji, the cost of living was rising. Indigenous Fijian workers, along with the formerly indentured Indo-Fijian workforce, chafed under the exploitation of the colonial, capitalist system. Some workers, like unionist Apisai Tora, had been radicalised by the experience of fighting in WWII and returning to continued hardship at home. It was Tora’s union, the newly-formed Wholesale and Retail Workers General Union (WRWGU), which launched the oil workers’ strike of 1959.

It began on 7 December. The union rejected an offer from their employers, which included only a minuscule pay rise and didn’t address any of the workers’ other demands around working hours, holiday pay, and sick leave. With their hands on the fuel supplies of the country, the strikers were able to bring many aspects of everyday life to a halt. In just over a week, the strike mobilised not only oil workers and drivers, but also huge crowds of supporters. Thousands picketed petrol stations, protested in city centres, and scuffled with police.

In his article “Class Struggle in the Pacific”, socialist Vinil Kumar describes this as “the first urban multi-racial strike by Indo-Fijian and indigenous workers in the country’s history,” demonstrating “the potential economic power of the growing urban working class and its ability to rally mass support”. This article draws heavily on Kumar’s article, with thanks.

Colonial History

Fiji was annexed by Britain in 1874, with the consent of some of the country’s chiefs. As Kumar writes,

In the late 1860s and early 1870s, armed rebellions known as the Kai Colo waged a struggle against the colonising power, but were ultimately defeated by troops and armed settlers from Australia, and armed Fijians from the eastern regions. A Great Council of Chiefs was created in 1876 which enshrined their power as the figureheads of the colonial state.

This power would come to bear in the 1959 strike.

In 1879, the colonial government brought in workers from India under a system of indenture known as Girmit, another form of brutal colonial exploitation. These workers became the main source of plantation and urban labour.

Colonialism, racism, and exploitation were sources of oppression shared between Indo-Fijian and indigenous workers. Meanwhile, the social and economic structures of colonial, capitalist Fijian society created tension between them. The leasing of Fijian land by freed Indian labourers-turned-farmers was a source of friction, often deliberately stoked and exploited by the colonial administration and capitalists.

The oil workers’ strike of 1959 was a culmination of all of these political forces, bringing Indo-Fijian and indigenous workers up against the colonial administration, the local ruling classes, the exploitative capitalist system, and entrenched racial injustice and division.

A history of struggle

This was hardly the first mass strike in Fiji.

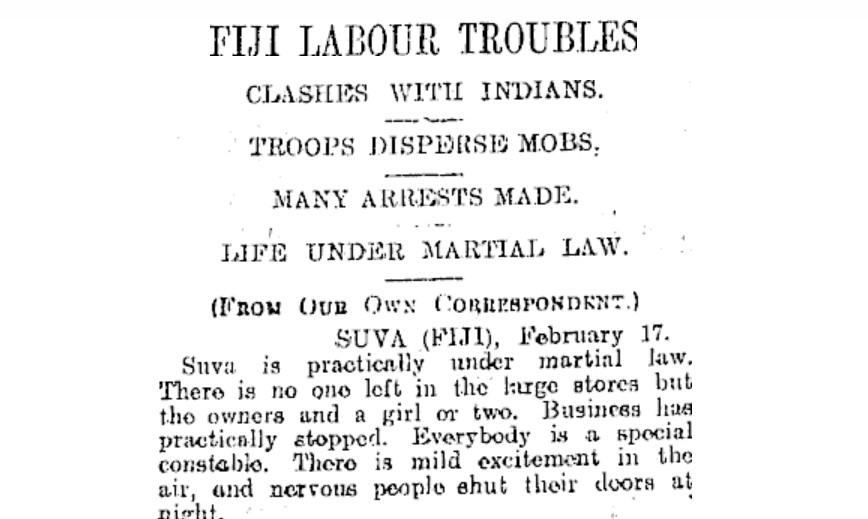

In 1920, the remnants of indenture were abolished. That January, (predominantly Indo-Fijian) workers at the Public Works Department in Suva initiated a strike against an increase in their working hours to 48 hours a week. Within a day, the bosses conceded to this, but rather than retreating, the workers pushed for more. The strike spread to Nausori, Rewa, and Navua. Thousands of sugar industry workers took part, bringing towns to a standstill. The colonial press called it “martial law”, and the Indian Women’s Association was labelled “Bolshevist” for leading crowds to physically confront scabs.

“We do not get enough to satisfy our bellies”, the strikers declared, demanding a pay rise in line with rising living costs. It was clear that they were also protesting their oppression at the hands of Europeans, directing their anger at racist bosses, business owners, overseers, and officials. In Suva, hundreds rioted in protest against a European hotel owner who beat his Indian servant and abused passing Indians.

The government armed European and indigenous Fijian strikebreakers and called on international assistance. The Australian government sent a warship. Another warship, from New Zealand, was delayed when workers refused to load it. Though the Fijian strikers defended themselves fiercely, the strike ended after just over a month. Along with force, political manoeuvring had been deployed. As Kumar writes, the end of the strike came partly due to “the efforts of a wealthy Indian planter and nominated member of the Legislative Council who secured a return to work and the banishment of one of the strike’s key agitators”.

Militancy and anti-imperial sentiment persisted, with a six-month shutdown of the sugar industry following the next year. In 1943, Indo-Fijians refused to fight for the British Empire, instead launching strikes across cane-growing districts. Once again, the Fijian government enlisted forces from Australia to help crush this rebellion.

Solidarity and Division

The colonial government feared that the Indo-Fijian workers’ struggle could inspire sympathy from indigenous Fijians. During the 1920 strike, Kumar writes, “Fijian labourers in the sugar industry sympathised with the strikes and also began to demand higher wages for themselves”. Enlisting indigenous Fijians as special constables and strikebreakers was one way to militate against this, though, as Kumar writes, “even the scabs brought in by CSR began to turn against the company after experiencing what it was like to work for them”.

To strengthen their position, the colonial administration painted themselves as defenders of indigenous Fijian society. This intensified after the strikes and protests of 1943, which provoked Europeans to rail against the “disloyalty” of the Indian population. European hotelier JJ Ragg addressed parliament in 1946, denouncing the “great increase in non-Fijian inhabitants” and calling for Fiji to be “kept as a Fijian country”.

Despite these attempts at divide and rule, the 1959 strike provided a glimpse of the joint struggle that the colonial administration feared.

Scenes from the Strike

Along with Apisai Tora, another leader of the strike was James Anthony, of Indian, Irish, and Polynesian descent. Anthony had been influenced by Australian communist Kevin “Big Jim” Healy, who was living in Suva at the time.

Their union covered oil workers at Suva’s Shell and Vacuum Co. depots. Pickets at these depots were dramatic. As Kumar describes:

On the morning of 9 December, trucks fanned out across Suva to supply fuel to petrol stations under police escort. Anthony was at one petrol station when supplies arrived, and mobilised a crowd of 400 people in protest. At a second petrol station, a crowd of Fijian and Indian protesters gathered and formed a human barricade to stop queues of cars from driving up to the pump. Indian and Fijian drivers were persuaded to show solidarity by not refuelling. By the time the police arrived, only the European drivers remained. Staff abandoned a third petrol station and when a white Shell employee tried to take over operations, demonstrators sabotaged and shut down the pumps by removing the fuse box. The manager of a fourth petrol station fled when protesters arrived, telling the police that they could serve customers themselves. All throughout the city, bus drivers were confronted and the whole bus network was paralysed. Taxi drivers joined the strike, some abandoning their vehicles in the petrol queues or in the city with “on strike” scrawled across their windscreens.

Here is one police officer’s account of a mass meeting, called by Anthony at 5 pm that evening:

When we got there, the bus stand was absolutely full of people, women and children predominating. I think they were very excited indeed. I don’t think they were alarmed. In fact, most of them seemed to be enjoying the situation immensely. There were crowds surging from one side to the other, singing nothing in particular – three cheers for this, that and the other… There were peals of very high pitched laughter. I did not know what to make of the whole thing.

When initial attempts to disperse the crowd were laughed off, the police resorted to batons and tear gas. The crowds scattered and regrouped. Barricades were built, groups of youths scuffled with cops throughout the night, and unrest spread across the island.

Diffusing the Strike

On 10 December, the police granted permission for a mass meeting. Expecting to hear from union leaders, strikers were instead addressed by three of the highest chiefs in Fiji, including Ratu Kamisese Mara, who would go on to become the country’s first prime minister and then president. Also speaking, was an Indian member of the Legislative Council, BD Lakshman. These figures of authority were deployed to diffuse the strike, admonishing the strikers.

Over the next two days, the chiefs continued to denounce the strike at meetings across the island. Oil workers and taxi drivers continued their strike, but skeleton bus services resumed and supply chains began to restart as more workers, especially indigenous workers, gradually returned to work. Kumar writes that “the Fijian president of the WRGU was also impacted by these arguments”:

He encouraged Anthony to seek medical attention for exhaustion, then immediately called in Mara, who introduced union delegates to company representatives and negotiated a settlement on the company’s terms. By the time Anthony returned, most of the union’s executive had ratified the deal and he eventually relented.

Making Waves

Resounding victories are not the only moments worth remembering. The world we live in today is shaped by the struggles of the past, and the class fighters of Fiji are an important part of our political whakapapa. The forces that contributed to the 1959 strike’s demise also had a lasting impact in Fiji, as ISO member Lily Atu described in a recent talk, with ethnic division shaping the politics of the military coup of 1987.

Just as the past impacts the present, when workers make waves in one country the ripples are felt on distant shores. The ruling class understands this interconnectedness, which is why the governments of Australia and New Zealand did not hesitate to respond when the colonial government in Fiji called on their aid to crush striking workers.

Today, the New Zealand ruling class continues to collaborate with their international counterparts to undermine the safety and self-determination of workers in the Pacific, whether it is through RIMPAC war games, Five Eyes spy networks, coercive aid arrangements, or exploitative trade deals. In response to global protest movements for peace and justice, governments around the world are working together to tighten their hold over their populations.

Reading this history, we would do well to take inspiration from the boldness and unity of the Fijian workers in 1959, and also from the solidarity of the New Zealand dock workers who refused to load the warship heading to break their strike in 1920. It is through practical acts of solidarity like this that we have the potential to turn the tide of struggle in favour of our comrades abroad.

Learn more

Vinil Kumar’s article “Class Struggle in the Pacific” can be read at marxistleftreview.org

Check out Lily Atu’s talk Resistance in the Pacific on the ISO Whanganui-a-Tara YouTube channel.

Image: Reporting in the Otago Daily Times of the 1920 Public Works strike, via Papers Past.