Confronted today with dismal Right Wing governments at home and overseas, it’s easy to feel powerless. But mass popular movements can beat back governments – especially when these are backed up by active support from workers and unions. In fact, we’ve beaten the government in Aotearoa many times before. Sometimes we scored quick victories. Other times, the success of a mass movement only became apparent years later.

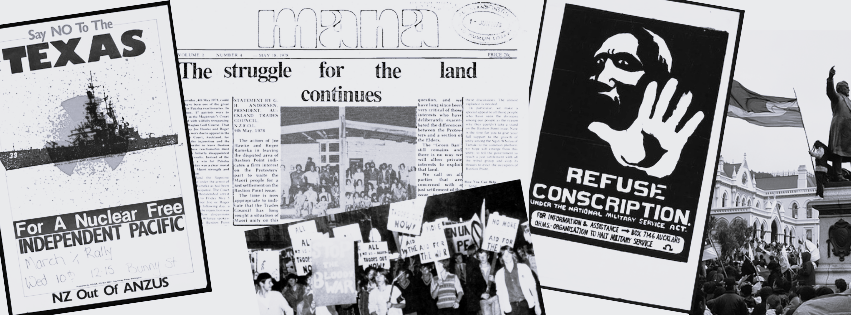

The history of successful mass struggles is usually covered up or, if it’s too big to hide, the history gets rewritten to make it seem like the success was due to some beneficent politician or state institution. With the amazing Hīkoi Mō Te Tiriti and Palestine solidarity protests still resonating across the motu, here are a few past examples to show what we can achieve.

#Landback

The colonisation of Aotearoa caused the alienation of 95 percent of Māori land. Treaty settlements have resulted in the return of land, although the amount of land returned and compensation paid is a pittance. Historian Vincent O’Malley calculated in 2018 that, “Treaty settlements typically return 1 to 2 percent of what was lost”. What is less widely known is that the return of land through the Waitangi Tribunal started because of mass mobilisations and industrial action by trade unionists.

The Waitangi Tribunal was established in 1975, as a result of pressure from a rising protest movement which culminated in the 1975 Land March. For its first ten years, it couldn’t examine breaches of Te Tiriti which occurred before that date, rendering the Tribunal largely useless.

On 5 January 1977 Māori from the hapū Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei, supported by communists and other activists, began an occupation at Takaparawhau Bastion Point. This last remaining block of Māori land in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland had been confiscated by the government in stages from the late 1850s until World War Two. In 1976, the National government under prime minister Robert Muldoon announced plans to sell it off for an up-market housing development. Māori demanded its return.

For 506 days, the occupiers resisted eviction. The Auckland Trades Council, the city’s union leadership, declared a “green ban” on the site, so that no union member would be allowed to build Muldoon’s mansions. On 25 May 1978, Muldoon ordered the New Zealand Army, backed by Air Force helicopters, to invade Takaparawhau and attack the people. The operation was later described as “the largest peacetime force of police and army in recent history” by Māori Affairs Minister Pita Sharples. But the green ban remained, and the mansions didn’t get built.

The land sat vacant until a law change in 1985 enabled the Waitangi Tribunal to investigate historical breaches of Te Tiriti. In 1987 the Tribunal recommended the return of Takaparawhau to Ngāti Whātua. The government, even after deploying military force, accepted that it was beaten. A decade on from the occupation, mass struggle backed by industrial action forced the return of the first block of Māori land under the Treaty settlements process.

To find out more, read: Remembering 1978…and 1943 and Ihumātao: a Struggle for Justice

No nukes!

Aotearoa’s nuclear free foreign policy has become part of this country’s national mythology. This mythology contains elements of truth, overlaid with ruling class ideology. Clips of Labour Prime Minister David Lange at the 1985 Oxford Union debate regularly resurface in the media. His famous quip that he could “smell the uranium on the breath” of a heckler made him look like an anti-nuclear champion. It reinforces the commonly-held view that he was the one who led Aotearoa out of the ANZUS nuclear alliance with the United States. In reality, Lange fought against the people who made Aotearoa nuclear-free.

The first nuclear warship to be welcomed to our waters was the USS Halibut, invited by Labour Prime Minister Walter Nash in 1960. Three more followed in 1964. When visits resumed after a hiatus in 1976, they were met with mass protests. As the USS Truxtun sailed into Wellington harbour on 27 August that year, waterfront workers launched a strike which lasted for the six day duration of its visit. No cargo moved. No inter-island ferries sailed. The Truxtun was unable to berth and had to anchor off shore.

Other Wellington workers also took strike action in protest, including the cleaners at the US embassy. The USS Long Beach got the same reception when it visited Auckland two months later.

Demonstrations grew in size with each visit. On Hiroshima Day 1983, as the USS Texas lay berthed in Auckland, 50,000 people took to the streets in protest. The mass movement shifted public opinion. In 1979, polls showed 61 percent of people willing to allow visits by nuclear armed warships. By 1984, 57 percent were opposed.

Propelled by the mass movement, delegates to the 1983 Labour Party Conference voted for a policy that: “The next Labour Government… will continue to oppose visits to New Zealand by nuclear powered and/or armed vessels and aircraft.” As Lange later admitted in his book, Nuclear Free – The New Zealand Way, he fought against it. “I argued against withdrawal from the alliance at party conferences and delegates hissed in ritual disapproval.” Elected as Prime Minister the following year, he defied his own party and told US secretary of state George Schulz, “nuclear-powered vessels which were proved safe and were not carrying nuclear weapons would be allowed to visit”. According to US ambassador H. Monroe Browne, Lange asked him to wait six months for the public to “cool off” and then restart the ship visits.

It was only the strength of the anti-nuclear mass movement, when the news broke of a planned warship visit in 1985, which forced Lange’s hand, defeated US imperialism and ended Aotearoa’s participation in the ANZUS nuclear military alliance.

To find out more, read this 1995 article: We stopped nuclear ships – we can stop French tests

Ending Conscription

It’s not widely remembered these days, but it used to be compulsory for young people in Aotearoa to join the military. All males had to register on their 19th birthday with the Department of Labour, and if your name was drawn in a ballot, off to the army you went. The campaign of civil disobedience to end conscription is one of the most spectacularly successful people-powered movements in this country’s history – scoring complete victory in little over a year.

The campaign began in Pōneke on 22 February 1972, at a small meeting of students in the Victoria University Students Association building. They settled on a name, Organisation to Halt Military Service or OHMS, being a pun on the unit of electrical resistance (ohms) and the stamp on official government postal envelopes at the time, On Her Majesty’s Service.

National chair of OHMS, Robert Reid, recently recalled that “it was no use being an individual martyr for the cause and it was necessary to build a nationwide movement of 19 year olds refusing to register for military service, even if this lead to huge fines, which if unpaid would lead to prison sentences”.

The main strategy was one of non-compliance. Many young men, on reaching the age of 19, broke the law by refusing to register for military service. For this, OHMS co-founder Geoff Woolford, a first year teacher at Taita College, was sent to prison.

As the campaign continued, other young men who had already been forced into training deserted military camps to join the new group of resistors. As OHMS grew, it forged links with Māori activist groups like Ngā Tamatoa. A 19-year old Tame Iti was one who refused to register.

OHMS found imaginative ways to resist. They found that filling in false compulsory military training registration forms, giving names like Micky Mouse or Prime Minister Keith Holyoake, completely disrupted the system. The campaign also included hoax bomb threats, setting off fire alarms and smoke bombs to disrupt the conscription ballot at the Labour Department head office.

The law requiring compulsory military service was repealed in 1973. Although OHMS claimed the victory, veterans of the anti-conscription campaign are quick to acknowledge that the power to win came from the mass protests against New Zealand’s involvement in the US war of aggression in Vietnam. These peaked with huge nationwide demonstrations on 30 April 1971, backed by the trade unions, which drew 35,000 people onto the streets.

To find out more, watch: OHMS! Protest! – A Celebration of Resistance

Stopping Health Privatisation

David Seymour’s ambition to privatise our public health system isn’t the first time that a Right Wing government has tried it. When National was elected in 1990, it set about transferring ownership of our hospitals to companies called Crown Health Enterprises. In 1992, the Government started charging all public hospital patients and moved to break the power of unions in the health sector. Labour Party leader Michael Moore said, “the introduction of user part-charges marked the second stage of the Government plan to privatise health.” Maurice Williamson, the associate Minister of Health, publicly refused to rule out privatising public hospitals after the 1993 election.

The government’s plans were met with a mass revolt. The Coalition for Public Health brought together a vast array of opponents including the country’s biggest trade unions, the Public Service Association and Engineers Union, medical workers organisations, nurses’ unions, and many community and religious organisations that spanned from the National Council of Women to the Anglican Church.

Protests took place outside hospitals from Whangarei to Timaru in 1992 to mark the last day of free hospital care. Wellington Hospital nurses defied orders from their managers to issue invoices to patients, and all the unions on site resolved to “support any staff disciplined for refusing to invoice patients or collect money.” The Service Workers’ Union, one of the largest in the country, urged their members to boycott the hospital charges, and offered legal support to boycotters if they needed it. Hospital staff from laboratory workers to cleaners and nurses went on strike. Doctors took strike action for the first time.

By April 1993, the number of New Zealanders with unpaid hospital bills had swollen to more than 20,000. Prime minister Jim Bolger sacked the Health Minister, and his replacement announced that charges for hospital stays would be scrapped – although outpatients would still have to pay for hospital appointments. The boycott continued.

By 1997 there was a non-payment level of at least 25 percent and 50,000 boycotters were being pursued by debt collectors. The last plank of the privatisation plan had to be abandoned. Once again, a people-powered mass movement had beaten the government.

To find out more, read: A social movement history of public opposition to New Zealand’s health reforms, 1988-1999