Parliamentary elections took place in France over two rounds of voting on 30 June and 7 July. They followed elections to the European Parliament on 6-9 June that registered further advances for the far-right and fascists. In Germany AfD (Alternative for Germany) came second with 15.9 percent of votes. In Austria FPÖ (Freedom Party of Austria) came first with 25.4 percent. In the Netherlands PVV (Party for Freedom) came second with 17 percent. In Italy Brothers for Italy came first with 29 percent. In Spain Vox came third with 9.6 percent. The most disquieting results were in France where Rassemblement National (National Rally, formerly National Front), came first with 31.4 percent of votes, which was more than twice that of President Macron’s Ensemble group in second place.

The main question of the snap parliamentary elections was would National Rally (RN) form a government under President Macron? To huge relief this outcome was averted with the RN pushed to third place. The party that won the most seats in the Assemblée nationale was, to the surprise of many, the hastily-formed left coalition: Nouveau Front Populaire (New Popular Front), consisting of Jean-Luc Mélenchon’s La France Insoumise (LFI), the Socialist Party, the Communist Party, Greens and other lefts, including the Nouveau Parti Anticapitaliste – L’Anticapitaliste (NPA-A). As the NFP have the most seats, although not a majority, it has the strongest claim to form the government; and Mélenchon has the strongest claim for Premier ministre as within the NFP LFI won the most seats. However, at the time of writing Macron has ignored the election result and the previous government continues on a provisional basis.

Under the French electoral system, candidates that obtain an absolute majority in the first round of voting are elected. If no candidate obtains a majority there is a second round run-off between the top two candidates and any that obtained at least 12.5 percent of votes of in the first round. Traditionally, left parties agree to stand down in the second round in favour of unity behind whichever left party got the most votes in the first round. The tactic is taken by the right. In this year’s election, to stop National Rally winning, there was mutual withdrawals of candidates by NFP and Ensemble. The NFP stood down in 134 electorates. Less responsibly, Ensemble stood down in 82 electorates.1 It worked, the immediate fascist danger was seen off.

The NFP was only formed on 20 June. It is a left reformist phenomenon similar to Corbynism. The far-left Nouveau NPA-A welcomed this development. Aurora Lancereau wrote:

‘On the one hand, the far-right bloc is growing stronger …. On the other hand, and fortunately, a left-wing bloc has formed, a surge of our social camp. The demand for unity at the grassroots level in the face of the threat of the RN taking power is indeed very strong, and has put pressure everywhere, including on the parties: this is how the formation of the New Popular Front (NFP) must be interpreted. It must itself be linked to recent and important unitary experiences, such as last year with the formation of the inter-union opposed to the pension reform, or in 2022 with the creation of the NUPES.’

‘Faced with this situation, the NPA-L’Anticapitaliste has decided to join the NFP for at least two major reasons. First of all, if we do not consider that the RN is equivalent to fascism, we consider that this party in power would be a first step towards the fascisation of the State. All the more so since Macronism, through its extreme authoritarianism, has put everything in place for this to be the case. It would be a qualitatively different attack and an extreme step backwards for the social movement, especially for racialized people, women, LGBTI+ people. We must repeat this in the face of the leftist temptations of a part of the far left: the RN in power is not equivalent to Macronism in power, a fortiori to the PS. We must therefore take this danger seriously.’

‘Secondly, we must recognise that the pressure for unity within our class is extremely strong. Any position other than unity is very difficult to hear. However, if we must be one step ahead of the masses, it is only one step. And this is all the more so since the NPA has been calling for unity for months and has been perceived as one of its main architects. However, there is a stake in the left winning: for the extreme right to lose and for the left to remember that it can win, which will help rebuild class consciousness.’2

The first round of voting on 30 June saw National Rally gain the most votes and, where not elected with an absolute majority, were in pole position in many areas to contest the second round. On the following day the NPA-A published an appeal and produced it as a leaflet. It warned of the grave danger of the extreme right. The NPA-A said:

‘The surge of the left around the New Popular Front is the only good news from this first round. Its significant scores are above all the fruit of a unity that set hundreds of thousands of people in motion to demonstrate and campaign.’

‘The main issue of the second round remains to prevent the far right from coming to power in a few days, an essential objective for our social camp. We know that the policy defended or implemented by the right, in particular Macronism in power, has largely contributed to paving the way for the RN, by taking up some of its measures and helping to give it legitimacy. However, between two dangers, we must first do everything to eliminate the most important and most immediate. Also, in view of the immediate interests of populations from immigrant backgrounds, of the entire world of work, of the defense of rights and public freedoms, it is imperative this Sunday to beat the RN, its allies and its supporters, preferably with a good left.’

‘Beyond the second round, what was built at the heart of this campaign, a united and militant left, must continue …. To do this, we must strengthen the unity of action of the entire left, from the base to the top. Be together and fight side by side: demonstrate against the extreme right and defend ourselves against the attacks of fascist groups, resist antisocial, discriminatory or authoritarian measures, police and racist violence, sexist and sexual violence, defend the increase in wages and social benefits, the return to retirement at 60 at full rate, keep alive internationalist and anticolonialist solidarity with Palestine, Ukraine or Kanaky and more generally with all the peoples who are victims of French imperialism. It is by mobilizing, all together, that we can change lives.’3

After the second round the NPA-A came out for the continuance of the NFP and the demand that its programme be implemented.

‘Sunday was marked by a surge, a popular vote that allowed the candidates of the New Popular Front to come out on top. It is also a reprieve, because although the immediate danger has been averted, the extreme right – which has won around fifty additional deputies – is progressing and remains a threat.’

‘The main lesson of this second round is the setback suffered by the National Rally (RN). The defeat of the hundreds of fascist, racist, Islamophobic, and anti-Semitic candidates that the RN had presented is a relief for racialized people, women, LGBTI+ people, and workers.’

‘This setback was the result of the rallying of the entire political, union and associative left, but also and above all of the electoral mobilization at the base of large sectors of the working classes, in particular racialized people and youth, behind the New Popular Front (NFP). This emergence of the united left allowed the election of 195 NFP and related deputies, including 78 for La France Insoumise. All were elected on a program that breaks with Macronism in the service of the ultra-rich…’4

Writing between the two rounds, John Mullen, a Paris-based supporter of LFI gave a flavour of the atmosphere of the election period.

‘Left parties, but also trade unions, women’s rights groups, charities, and pressure groups like Attac or Greenpeace are pulling out all the stops, leafletting railway stations, and contacting all their supporters. Eight hundred thousand demonstrated in over 200 towns in a trade-union initiative; women’s rights groups organised marches in dozens of towns. Every day there are rallies, called by youth organisations or by the radical press and so on. On 3 July, a huge outdoor concert in Paris heard from Nobel prize winning novelist Annie Ernaux and dozens of speakers. Appeals against the far right are surging from unexpected circles. Eight hundred classical musicians signed one appeal, 2500 scientists another, and there have been similar initiatives from social-science journals, university chancellors, rappers, and rock musicians. Star footballers, cyclists from the Tour de France and many more have added their voices. Academic societies, the Left press and the theatre festival in Avignon have organised appeals or events.’5

The NPA-A’s participation in the NFP to date has been a non-sectarian policy. The unity of the main forces of the left met the needs of the working class and oppressed at a specific moment. The immediate danger was of the fascists getting into government. They have been thwarted for the time being, and the left has bought precious time to organise. Of course, trust cannot be placed in the reformists; the NPF could fall apart at any time. However, as long as the NFP is inspiring working-class unity, the NPA-A is, in my opinion, correct to continue with the unity perspective and to demand that the left-wing programme of the NFP is implemented.

Tactical differences between revolutionary left groups towards the election and its aftermath have been and continue to be aired in France and elsewhere. Should revolutionaries join the NFP? Which party should people vote for? Should the NFP have stood down candidates? Should revolutionaries demand that the NFP programme be implemented? Other French groups have adopted different polices to those of the NPA-A.

Lutte Ouvrière (Workers’ Struggle) stood in over 550 electoral divisions – a mammoth effort – but only achieved 1.1 percent of votes cast and did not qualify for the second round anywhere. For the second round LO told its followers that they could vote for the NFP if they wanted to, or abstain.6 In other words, LO was agnostic on whether fascists got into parliament, and potentially government. LO’s sectarianism was sterile and their policy made them an irrelevance at best, irresponsible if taken seriously.

The NPA underwent a split in 2022, hence there exists the NPA L’Anticapitaliste and NPA Révolutionnaire: L’Anticapitaliste and Révolutionnaire being the name of their respective newspapers. On 14 July the NPA-R published a resolution put up by their leadership for discussion.7 Like LO, they oppose the NFP. They state:

‘The union leaderships, particularly the CGT, had called for a vote for the NFP in the first round. The NPA-Revolutionaries activists in the unions opposed it … to defend the necessary independence of the unions from this left-wing government coalition, which immediately linked its fate to that of Macron through the “republican front.”’

The republican front refers to Ensemble and the NFP stand downs to block the fascists from becoming the largest party in the Assemblée nationale. The NPA-R proposed an electoral agreement to LO, but were rebuffed. The NPA-R stood 29 candidates and got miniscule votes. Their proposed policy after the election is to work together with groups that have not joined the NFP – chiefly with LO. Like LO, the NPA-R did not make any contribution to the victory won against the fascists.

Political differences over what has happened in France are being aired internationally. This review confines itself to the revolutionary left in Britain.

On 10 June, the British Socialist Worker, newspaper of the Socialist Workers Party, had an interview with French co-thinker Denis Godard:

‘The conclusions must be drawn. Blocking the fascist route does not pass through various kinds of electoral manoeuvres and compromises with racism.’

‘It is only possible to block the route to fascism through the fight against racism in unity and in solidarity with migrants. And we need anti-fascists rooted in the neighbourhoods and workplaces.’8

Godard downplays participation in elections and falsely counter poses electoral activity to work in communities and trade unions.

On 15 June, Socialist Worker’s Charlie Kimber took a similar line.

‘Millions of people will feel it’s right to vote enthusiastically for the Popular Front. But the key mobilisation is not in the elections but at the base, to fight fascism whoever wins at the polls.’9

Kimber is correct in a general sense, but he does not take account of specific situation at the time of the French legislative elections.

Writing on 30 June, Kimber recognised the real danger of the RN getting into office, but did not draw the necessary conclusions. He said it was wrong for the NFP to include François Hollande of the Socialist Party, who attacked the working class when President 2012-2017. The criticism of Hollande may be valid, but the NFP cannot dictate to the Socialist Party which of its members can be admitted. To do so would be to exclude the Socialist Party from the NFP and weaken the united front. Kimber stated: ‘You can’t build an alternative to the RN around such people, yet the NPF makes such concessions.’10 The answer to Kimber is that concessions are necessary to form political alliances. At a particular point in time, when the RN had come first in the European elections and were threatening to do the same in the French general election and get into government, the question to be asked was which policy would serve the working class best? Would it be a united front of the entire left, including the Socialist Party on its right flank, or a narrower left wing front and the left vote split between the SP and the radical left.

Writing between the two rounds of voting, Kimber attacked the NFP for standing down in the second round in those constituencies where Ensemble had the better chance of beating the fascists.11 Kimber must be answered again: at that moment it was necessary for mutual standing down of candidates by the NFP and Ensemble to prevent the fascists from winning in great swathes of the country where they were in first place in the first round.

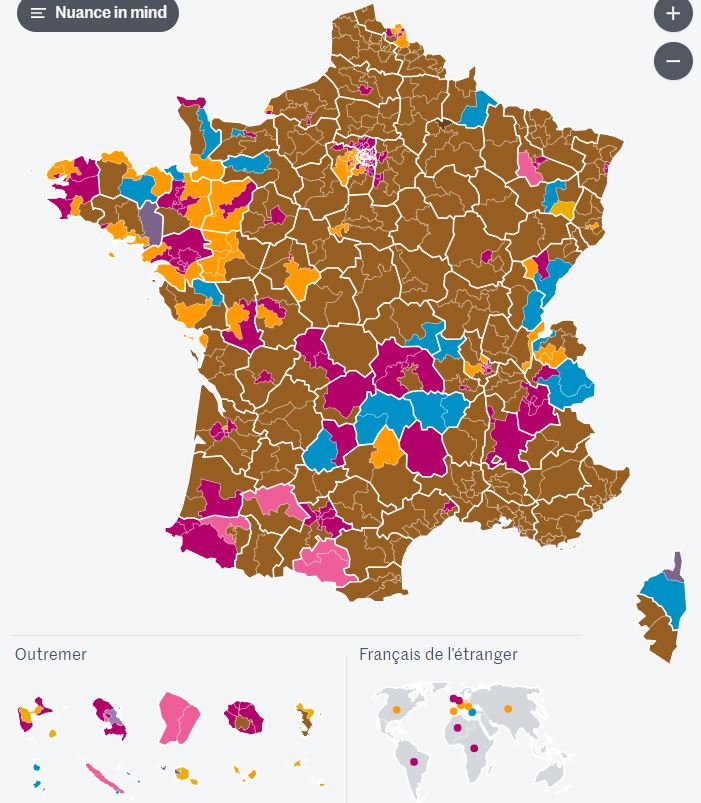

The brown constituencies in the first map below are where the RN were in first place after the first round of voting. The purple and yellow areas are where the NFP and Ensemble were in the lead. The second map show the results after the second round.

Source: https://www.lemonde.fr/

Source: https://www.lemonde.fr/

An alternative to the SWP’s position on the British revolutionary left comes the rs21 group which has published two articles on the French elections by Ian Birchall, a veteran Trotskyist in the international socialist tradition. Birchall wrote:

‘The demonstrations have been enormously important, actively involving thousands of citizens. But it is quite wrong to juxtapose demonstrations to voting, to argue that mobilisation at the base is all that matters and that elections are irrelevant. Of course, in the long term voting alone cannot halt fascism. But at the present juncture voting was the key factor. The demonstrations inspired and mobilised people to vote.’

‘In fact the NFP has been crucial to the halting of the RN. By bringing together the great majority of forces on the left and centre left, and organising withdrawals for the second round of voting to get wherever possible a single focus against the RN, it made the relatively good results on Sunday possible.’

….

‘Those who criticise the NFP have to ask themselves if the RN could have been blocked without it. The RN presented a serious threat, especially to those inhabitants of France who were migrants or were descended from migrants. Among other things it proposed the refusal of medical care for undocumented migrants, offering social housing to French nationals only, and excluding people with dual nationality from public service jobs. To forget this, to fail to see the defeat of the RN as the overriding priority, was to fail to see the situation from the standpoint of the most exploited and oppressed, notably Muslim women, who faced the possibility of having their lives wrecked by a ban on the hijab.’12

Clear differences on the legislative elections exist within the revolutionary left in France and Britain. A key question is the application of tactic of the united front, which will be taken up in due course in a separate companion article to this one.

Header Photograph by Martin Noda / Hans Lucas

France, Paris, 2024-07-07. Rassemblement apres la victoire de la gauche lors du deuxieme tour des legislatives. Photographie de Martin Noda / Hans Lucas

1: Le Monde

2: Aurora Lancereau, ‘New Popular Front: a tool for rebuilding a left of struggle’, in L’Anticapitaliste Revue, 23 June. NUPES was the left-wing electoral bloc formed for the last legislative elections in 2022. Google translated, as are all following quotations from French sources.

3: ‘Stop the far right, strengthen the united and militant left’, NPA-A, 1 July.

4: ‘The RN defeated, the program of the New Popular Front must be implemented’ NPA-A, 9 July.

5: John Mullen, ‘Fascist breakthrough in first round of elections in France: an anti-capitalist perspective’, Counterfire, 5 July. Counterfire also has a link to a Youtube video of a talk by Mullen that is informative on the LFI. See https://www.counterfire.org/article/john-mullen-eyewitness-from-france/.

6: Editorial, ‘There will be no way out without a revolutionary communist workers’ party’ Lutte Ouvrière, 7 July.

7: ‘Political resolution of the CPN of the NPA-Révolutionnaries of July 13 and 14, 2024’. CPN stands for National Political Committee.

8: Denis Godard, ‘How can anti-fascists win in France’.

9: Charlie Kimber, ‘Hundreds of thousands march against fascism in France’.

10: Charlie Kimber, ‘Urgent tasks for left after fascists win French election first round’, Socialist Worker.

11: Charlie Kimber, ‘French elections: Why the New Popular Front standing down candidates won’t beat the fascists’, Socialist Worker, 3 July.

12: Ian Birchall, ‘The French far right pushed back – for now’, rs21, 11 July.