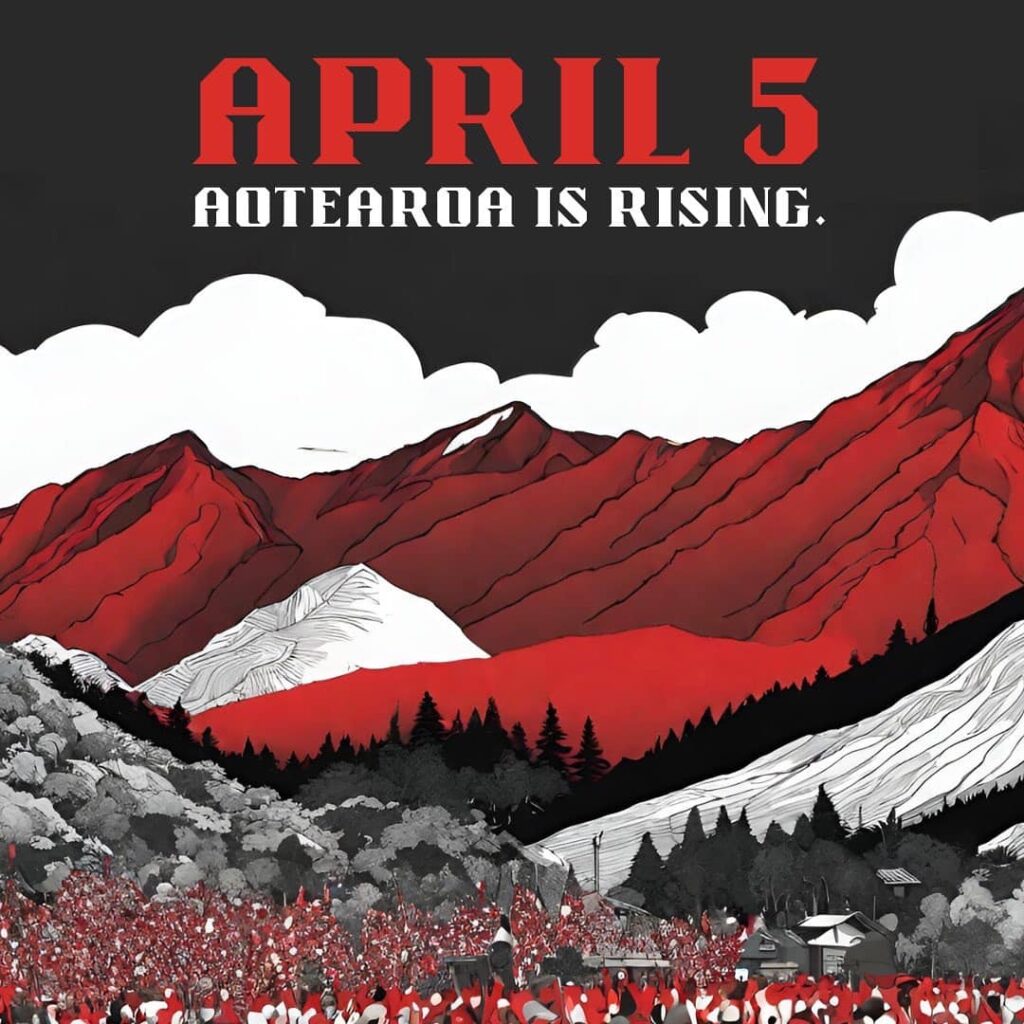

School strike for Climate are mobilising students once again to strike against climate change. The political demands connect the issues of climate justice with Toitū te Tiriti, Freedom for Palestine, National’s plans to fast-track environmentally damaging projects, amongst others. Josh O’Sullivan argues for why we need to dismantle capitalism – root and branch – to deal with climate change.

Dealing with climate change is a complex topic. The urgency of this crisis and what we are being told to do to deal with it by those in power are obviously counterposed. It is hard to be presented with such a dire situation and only be told about miniscule individual actions such as using more public transport or recycling.

Our individual contributions are a drop in the bucket when it comes to dealing with climate change, and proposed technological solutions lack the scale and speed necessary to actually deal with the problem. Even these technological solutions, such as carbon capture or more extreme suggestions such as geoengineering, are only viable in the eyes of the capitalist states as long as the ruling class can make profit from them.

Our personal climate impacts are not the main driver of runaway climate change. In the Carbon Majors Report, the Carbon Accountability Institute in 2020 calculated that 100 companies and the commodities they have produced are responsible for some 70 percent of the world’s historical emissions. The scale of the crisis is overpowering and it is nothing less than patronising to tell people to ride their bike or buy local seasonal foods to reduce their carbon footprint, when the vast majority of emissions come from industry. Collective action across our whole industrial sector is the only thing that can even make a dent in our woefully unprepared society. A planned economy that provides for the needs of people to ensure a just transition to a liveable future is desperately needed.

The conversation around climate change always seems to focus on our emissions, but the full reality of what we face is far larger than the amount of carbon dioxide being produced and put into the atmosphere. Our entire relationship with nature over the past 200 years has been predicated on an economic system that sees environmental damage as someone else’s problem, and profit as the only solution. Plastic and chemical pollution; open pit mining; deforestation; mono agriculture; overfishing; ocean acidification; the loss of biodiversity — all of these issues compound each other. At risk with the worsening climate crisis is not just our comfort, but access to the earth’s collective resources: water, land, and clean air; as well as the mass displacement of millions of people who will become known as climate refugees.

Previous and current governments in New Zealand have been hesitant to disrupt the economic paradigm adopted since the introduction of rogernomics and deregulation in 1981. Indeed, the productive capacity to do all the necessary work to mitigate and deal with the effects of climate change is the largest task our society has ever faced. Despite the reluctance to take steps such as building a Ministry of Green Works, it is still the state that has the capability to marshall the productive forces in society. Even simple recovery projects will need the hands of tens of thousands of workers repairing ecosystems, building back after natural disasters and regenerating nature if we are to survive.

There are even more radical options we could look at in the here and now: nationalizing extractive industries to prevent further extraction of carbon we cannot burn; building mass transit that actually works, rather than setting out a tender process to get the lowest bidder; renationalising the electricity system; ensuring water is used for human consumption here, rather than bottled and sold by a private company on the other side of the world; Ensuring that we have a working food plan, so that we are not building housing on the only place in the country that can grow our vegetables, or trying to run irrigation through a desert to farm dairy cows. Beyond that we would need banks to be nationally owned in order to fund these transitions away from things that bear the most profit – into other areas that bear the most sustainability.

But even all of these extreme, radical ideas do not change the fundamental nature of our economic system that ensures that environmental concerns are secondary to profit. There are no wilds left unconquered, everywhere we have transformed the last vestiges of nature into something man made, something designed to extrude profit. The common link between all of these issues is the fundamental relationships in the economics of our society, namely capitalism.

Capitalism’s disregard for the environment can be understood through a concept called the metabolic rift. In the simplest terms, the metabolic rift is a breakdown in the healthy functioning of the relationship between human society and nature, the metabolic process that human society depends on in both its external aspect—the exchange of material between human society and nature—and its internal aspect—the circulation of material within society.

Take the process of production; the making of goods occurs through people working, labouring, in the natural world. In pre-class societies, the two ends of that process — the natural resources and the end product — are related in a more or less direct and transparent way. The raw materials required for the production of basic necessities like food, shelter and so on were mostly sourced from the immediate surroundings of settlements.In this context it would be very obvious if the metabolism had broken down in some way—say by an area of land being eroded due to the excessive clearing of trees.

It would be similarly clear if the process of exchange of goods within the community broke down, and the health of one section of the population began to suffer as a result. With the emergence of class society, when a minority of the population came to live off the surplus produced by others, the link between the natural basis of human society and the lives of those who made the important decisions became more tenuous.

As Marx sees it, however, it’s only with the emergence of capitalism from the seventeenth century onwards that the link is severed completely. Even the wealthiest of feudal lords still had some connection to the land. Their power was bound with a particular estate. If the feudal lord failed to manage the land sustainably, if he logged all the forests, poisoned the waterways and so on, he would undermine not only the source of his material wealth, but his identity and being as a lord.

The alienation of the land—its reduction to the status of property that can be bought and sold—is what for Marx constitutes the foundation stone of the capitalist system. The wealth and power of the capitalist class doesn’t depend on their possession of this or that particular piece of property, but rather on their control over capital. Capital can include physical property, such as farmland, machinery, factories and offices, but it is by its very nature fluid and transferable. If a capitalist buys up some land and then destroys it, they can simply take the profits they’ve made from it and move their money elsewhere.

At the same time as it completely severs any semblance of connection with the land among the ruling class, capitalism also severs it among workers. The peasants under feudalism had a direct and transparent dependence on the land for their subsistence. But with this came a degree of independence that isn’t afforded to workers under capitalism. The peasants had to give up a portion of their produce to the lord, but outside of that they were relatively free to labour as it best suited them. And no matter how unfree they were in a political sense, their capacity to sustain themselves was at least guaranteed by their direct access to the land and their possession of the tools necessary to work it.

For capitalism to be put on firm footing, this direct relationship of the peasants to the land had to be severed. They were, over a number of centuries, forcibly “freed” from the land in order that they could be “free” to be employed in the rapidly expanding capitalist industries. Workers, for Marx, are defined by their lack of ownership of the means of production. They are no longer dependent on the land for their subsistence, but rather on the preparedness of a capitalist to give them a job and pay them a wage.

This process of the reformation of feudalism into capitalism, is also the same process repeated wherever capitalism found new lands to covet; new populations to bring into the labouring classes. This is the story of colonisation. In Aotearoa this same process of the alienation of land occurred, starting with the purchasing of land through the New Zealand Company, then the invasion of the Waikato and then the most effective method: through the Native Land Court. All of this to turn the land into capital, something that can be traded, sold and worked on, and also to force the Māori population into a low wage workforce on their own land. Everywhere capitalism has sprouted it has reforged the social relationships that existed previously into a relationship between those who have capital and those who only have their labour.

The fact that the capitalist class has no real incentive to protect the environment, and the working class has no control over it, lies at the heart of capitalism’s unique destructiveness. The “logic” of capitalism is one in which maintaining the health of society’s metabolism—either externally in its relationship with nature, or internally in its distribution of goods among the population—only features to the extent that it assists the accumulation of wealth by the ruling class. The one thing the capitalist class cares about above all else is profit. No matter what the consequences, whether on the natural environment, human health or anything else, if business owners can continue to expand their pool of capital, they will see it as a success.

Infinite growth on a finite planet is impossible, yet nowhere is this tautology being acknowledged. We cannot allow politicians to convince us to compromise so that the engines of profit and accumulation can continue to turn. Because there is no compromise with the laws of nature. Paraphrasing a tourism business leader I heard on RNZ today, businesses can’t turn green unless they are in the black. That is exactly the problem. We cannot bargain with papatuānuku to make sure our economy survives, or to give us more time to adapt. Change needs to happen now. The fight for indigenous self determination and Land back is an essential element for fighting for a survivable future. Colonised peoples have a living memory of existence before capitalism twisted all social relations to be mediated by the market. That memory of the respect of the land as our parent, we as kaitiaki of it, not ownership of it, must be at the center of any movement seeking to repair the metabolic rift.

It is a stark choice for our species in the next few decades, either we radically transform the very nature of society or we suffer the eventual extinction of our species. We need to talk about radical solutions, because we don’t have time for anything less. We need to dismantle capitalism.