Protect Otago – Save Our University

Brian S. Roper is an Associate Professor and former Head of the Politics Programme from the University of Otago. He is working on a book entitled – Neoliberalism’s War on New Zealand’s Universities – to be published by Palgrave MacMillan in 2024.

Here he responds to four key questions in relation to the proposed job cuts at Otago:

1) Why is the University of Otago in financial crisis?

2) What’s wrong with the Acting VC and Senior Leadership Group’s (SLG’s) proposed solutions to the crisis?

3) What should be done to protect Otago and save our university?

4) What kind of action do we need to take in order to build pressure on both the University’s senior leadership and the Labour Government?

1) Why is the University of Otago in financial crisis?

When the Acting VC made the announcement, the proposed ‘several hundred redundancies’ were justified in terms of a decline of student enrolments. The number of effective full-time students (EFTS) enrolled at Otago for 2023 (forecast to be 18,986) is down 0.99% or 188 EFTS compared with 2022 when there were 19,174 EFTS (https://www.odt.co.nz/news/dunedin/campus/perfect-storm-facing-university-otago).

This is a very small decline in enrolments but the ‘decline in student numbers’ line was widely uncritically reported in the media at the time. Senior leadership claim the budgetary crisis has resulted from total enrolments being down by 5% relative to their optimistic 2022 forecast for a 4% rise in total university-wide EFTS during 2023.

The truth is that this very small decline in enrolments, which has involved a decline of 677 domestic EFTS offset by a 490 increase in international full-fee students, is not the main cause of the financial difficulties being experienced by the university. By far the most important cause is the cumulative underfunding of New Zealand universities since 2011.

The TEU estimates that the cumulative underfunding of universities by the Key-English Government amounted to $3.7 billion from 2009 to 2018. (https://www.scoop.co.nz/stories/PO1811/S00242/restore-a-decade-of-lost-tertiary-funding.htm) This is widely accepted to be an accurate estimate. Among other things, this Government: reduced spending on student allowances by 27.8% from 2011 to 2016; raised the student loan repayment rate from 10% to 12% and set the threshold for starting repayment at 60.2% of the annualised minimum wage; allowed domestic tuition fees to rise by 25.5% from 2011 to 2016, and cut government funding for universities from 71% to 68% percent per student (Roper, 2018a: 26-31). Overall, government spending on tertiary education was reduced from 2.3% of GDP in 2010 to 1.6% of GDP in 2017 (TEU – as above).

Most university staff and students hoped that the Ardern-Hipkins Labour Government elected in 2017 would be better, but it has been even worse than the National Government that preceded it with respect to chronic underfunding of New Zealand’s universities. Allowing for inflation, and the Annual Maximum Fee Movement set at 1.7% for domestic students in 2021 and 2.75% for 2023, Labour has driven through the deepest annual cuts to funding of New Zealand universities since 1984. As Chris Whelan, Universities New Zealand (UNZ) chief executive points out, ‘‘Government controls or provides 77% of university funding. … In 2023 alone, that funding increased by only 1.6% at a time when inflation is running at more like 6.8%.’’ According to the Budget 2022 forecast figures, which have to be treated cautiously until we know the actual figures, the Government’s overall spend on tertiary education increased in nominal terms, that is excluding the effects of inflation, from $4.939 billion in 2022 to $5.328 billion in 2023. This is a nominal increase of $389 million or 7.87%. But the bulk ($381 million of $389 million) of this increase is directed towards student loans ($313 million) and student allowances ($68 million). This means, in effect, virtually a zero (0.16%) increase in nominal funding for tertiary education providers with CPI inflation peaking at 7.3% in June 2022 and still remaining high at 6.7% in March 2023 (Budget 2022 – Economic and Fiscal Update, p.147; https://www.stats.govt.nz/indicators/consumers-price-index-cpi/). It also means that the single largest increase in the Government’s tertiary education spend was to help students borrow more and get deeper in debt.

What enabled New Zealand universities to survive given sustained cumulative underfunding by both National and Labour governments, was a substantial rise in international full-fee paying students. For example, ‘International students made up 18 percent of the New Zealand student population at bachelors and postgraduate level in 2016, compared to 13 percent in 2008’ (MoE, 2017: 27). By 2018, 22.3% of all international students in New Zealand were studying at one of New Zealand’s universities. The tuition fees they were paying, amongst the highest in the OECD, amounted to $513.4 million (MoE, 2019: 10). This international student revenue stream was of crucial importance in view of the scale of government underfunding mentioned above. Once COVID hit, this revenue stream dried up. The Government did provide some additional support in 2020 and 2021, but not enough to offset the loss of this revenue stream. There was plenty of money for New Zealand’s largest corporations amongst its 2020 COVID support packages which amounted to $65 billion. The bulk of this money was channelled through employers rather than being paid directly to workers.

The combination of the border closures associated with the pandemic and chronic government underfunding has had a disastrous impact on tertiary education providers. Little wonder that five of New Zealand’s eight universities are currently experiencing severe financial distress. Otago’s financial crisis is thus just one instance of a wider crisis in the tertiary educational sector.

It’s worth noting the decline in enrolments experienced by several New Zealand universities is also just a manifestation of a long running trend. As a result of declining student income support, rising tuition fees (amongst the highest domestic fees in the OECD), and consequently, rising levels of student debt, participation in tertiary education has been falling to an alarming degree. By 2019, there were 124,556 fewer students studying at tertiary level than in 2005. In September of 2020, Labour broke its 2017 election promise to introduce three years of fee free tertiary education by 2024.

The excuse that the policy had not markedly increased enrolments deliberately ignored the big picture of the long-term correlation between declining student income support, rising fees, and rising debt, on the one side, and declining student participation tertiary education, on the other. Changing one small part of this toxic mix is not going to solve the problem of declining participation in tertiary education. It should be obvious that it will require, at the very least, fee free tertiary education, greatly increased provision of student allowances by increasing the ridiculously low parental income thresholds for eligibility, and a resulting qualitative decline in the amounts students have to borrow to complete their studies. Even better, would be scrapping the student loans scheme altogether and introducing the Universal Education Income advocated by NZUSA (https://www.students.org.nz/uei).

So this is the big picture, but there also has been one possibly significant internal driver of Otago’s financial crisis. This was the introduction of a centralised services model (SSR) in 2016-17. It is widely rumoured that senior management has spent somewhere from $30-40 million on management consultants and the introduction of SSR since 2015. I don’t know if this rumoured amount is true. I hope it isn’t. It would be good to get clarification from senior management as to what the real costs of introducing SSR and using management consultants have been since 2015. But it is clear from the figures that we have available that SSR has been an expensive failure. Senior management claimed that SSR would provide cheaper, better, more efficient administrative and service support – “doing better with less” – but in reality it has delivered neither the reduction in non-academic staffing nor a reduction of service and administration costs that management claimed it would. Of course, maintaining non-academic staffing levels is a good thing, the problem being that the substantial reduction of embedded administrative and service support has left most academics scratching their heads regarding what is going on in ‘SSR land’.

Finally, most staff remain sceptical about “the $60 million hole in the university’s $834.4 million operating budget for 2023” that is being used to justify the large-scale redundancies being proposed. Certainly, the very small decline of EFTS that has been referred to above cannot be the main cause of such a large budget blow out. Staff would appreciate more detail with respect to the specific components of that $60 million dollar figure.

2) What’s wrong with the Acting VC and Senior Leadership Group’s (SLG) proposed solutions to the crisis?

So far the solutions senior managers have come up with do nothing to address the main cause of the University’s financial crisis – chronic government underfunding. Far from effectively opposing this underfunding, in which this Labour Government is cutting funding for our universities to the bone, it is doing Labour’s dirty work for it. Instead of standing alongside staff and students in opposing government underfunding, it is proposing savage cuts to staffing and spending across many areas of the university. In doing so it is taking a stand- it is standing with the government – not with us.

Of course, it is good to see that the SLG has agreed to work with the TEU for a joint push to get more money from the government. It would have been better if they had been prepared to work with the TEU much earlier, given that the TEU at national level for several years has been asking the VCs group – Universities New Zealand – for a joint lobbying push for more government funding, while being repeatedly rebuffed. Given that the preparedness to work with the TEU has followed rather than preceded the announcement of proposed redundancies, it has the appearance of a tactical move to take some heat out of the situation.

Like all staff, I very much hope this is a false impression, and that the University management representatives make it clear to the Government that it is unacceptable to impose savage cuts in government funding for New Zealand’s oldest university, which performs all sorts of crucially important roles as a public educational institution, and that it will not comply in implementing them if government isn’t prepared to come up with a rescue package.

Secondly, this constitutes the biggest attack on university staff by management in the University’s history. It is an attack not just on those staff who may lose their jobs, but also on all of those staff who remain. They will face increasing workloads combined with declining employment security. This is particularly hard to take, especially given the huge effort that staff recently made to help get the University through COVID. Employment security for academic staff is particularly important given the long training period required to obtain an academic position. It is also important if the University is to fulfil its statutory obligation to act as a critic and conscience of society. In order to perform the role of public intellectuals, which occasionally involves speaking truth to power, academics need to know that their job is secure, even if what they say or write is unpopular with the powers at be.

Thirdly, the proposed cuts to staffing and spending also has negative implications for students. Most obviously, because cutting papers, programmes, majors, minors, and degrees gives students less choice and reduces the quality of their education. Losing so many talented, experienced, and knowledgeable academic staff will also reduce the teaching and research capacity of the university as a whole. Also, in view of the extreme financial pressures on New Zealand universities, the government is likely to allow universities to raise fees by substantially more than the 2023 figure of 2.75% – unless there is a substantial real increase in government funding per student. In other words, the costs of government underfunding may well be pushed onto students through higher fees.

Fourthly, Dunedin/Ōtepoti is a university town. It’s a city of around 134,000 people, of whom around 24,000 are either students or staff at the University of Otago. These proposed cuts could have a substantial negative impact on the local economy and employment within it. Then there are the multidimensional positive contributions that the university makes to the city – culturally, intellectually, and so forth.

Fifthly, having seen the effects of this kind of down-sizing elsewhere, many staff worry about the long-term negative impacts on the university- not only with respect to its teaching and research capacities, but also with respect to student enrolments in future years. They fear that it may initiate a downward spiral. As course offerings, degree options, and so forth, are cut, and teaching staff let go, this may make Otago less attractive relative to other universities, and so student enrolments may decline in future years, requiring further lay-offs, leading to further reductions in course offerings, fewer students, and so on.

3) What should be done to protect Otago and save our university?

At present, university management and the Government are engaging in buck passing. Senior management argues, correctly, that the Government is to blame because it isn’t providing the university with the money it needs to operate effectively. Meanwhile, the Government argues that it’s up to the university’s senior leadership to make financial and staffing decisions. In this way, both simultaneously dodge responsibility for the situation. But, in reality, both are responsible, even if the bulk of the blame should be directed towards the Government.

In the minds of the senior leadership, they are doing the best they can in order to ensure that the university remains financially viable. To be fair, and to its credit, senior leadership at Otago has up to this point been more reluctant than their equivalents at some other universities around the country to push through job cuts. Sustained chronic underfunding is forcing good people to do bad things that they would prefer not to be doing. But they now think that they have no other choice and are making the tough decisions that need to be made in order to ensure that university remains financially viable.

The problem is that all of this only remains true if one swallows – hook, line, and sinker – the neoliberal configuration of tertiary education. Neoliberalism locks managers at all levels of the organisation into income, expenditure, and profit/loss accounting. But there comes a time when it is important to step back from this and look at the bigger picture.

Otago is a public institution – it’s owned by the government and is mainly tax-payer funded. As such it is tasked with all sorts of crucially important roles that differ fundamentally from those performed by businesses in the private sector. Universities are not, and should not become, profit-seeking corporations. Among other things, they educate young people and help them realise their potential, of which equipping them with vocational skills is only one aspect of the educational process. Without wanting to exaggerate the importance of the latter, our society does need doctors, dentists, lawyers, engineers, scientists, accountants, public servants, policy analysts, historians, writers, artists, architects, geographers, and so forth.

As I write these words, I immediately start to think of everything I am leaving out and the impossibly long list I am trying to compose here. Afterall, what makes our universities so special – for staff, students, and the public – is precisely the vast range of what is researched and taught. For example, there are many specialists in departments within the medical school who I have never meet, but I know that their work is of vital importance, as the COVID-19 pandemic and all sorts of other health issues shows so clearly. In view of this, it is nonsense to suggest that one can “do better with less”. The truth is that less is simply less of all the good things that the university does.

Universities generate all sorts of positive externalities for the economy and society. University research and teaching contributes positively to technological innovation and development, the quality of investment decisions made by graduates in the private sector, the skills and productivity of workers, and so forth. By educating successive generations of talented and intelligent young people, they also help to sustain a democratic political culture, including providing independent critical analysis of inequalities associated with age, ableism, class, gender and ethnicity. They also have an important role to play as public institutions of learning in helping to overcome the destructive multidimensional impacts of white settler colonialism. Otago has laudable goals in this regard. In its Māori Strategic Framework, it quite rightly commits to achieve “equitable Māori participation and success rates in tertiary education”, “Championing an environment in which scholarship and partnership will flourish to advance Māori development aspirations”, and “embedding mātauranga Māori within the University’s core functions.” These goals will be harder to achieve if several hundred scholars are laid off.

For these reasons, and all those that I’m sure I’ve left out, it is not OK to hack and slash this treasured public institution of higher learning. The truly courageous path is not going with the neoliberal flow of profit and loss accounting, of taking the path of ruthlessly cutting staff and important areas of expenditure to achieve a substantial operating surplus. It might be an unpleasant path for those at the top – but it is not the most courageous path they could take. A better and more courageous path is to act to protect Otago and save our university by telling this Government that senior management will not implement the cuts it is trying to impose. The $60 million the University claims it needs to prevent the proposed cuts is not a lot of money relative to the Government’s overall expenditure (around $158.5 billion in 2023). With respect to the Government’s forecast total spend on tertiary education of $5.3 billion in 2023, it is only 1.2%. In relation to the university’s operating budget for 2023 of $834.4m million, it is only 7.9%. Therefore even if the Government does provide the $60 million required to avert job losses, it would still be far from fully addressing the short fall in government funding for Otago during 2022 and 2023 resulting from inflation in the 6.7% to 7.3% range. If this government can come up with $65 billion worth of support packages for business, workers and beneficiaries out of the normal budget cycle in response to COVID, then it surely can come up with $60 to save Otago from the long-term damage these job cuts will cause.

But if the government refuses to contribute this amount, then the response should then be to borrow. Think about it. The university is a publicly owned institution. University debt is de facto government debt, no matter how much Labour government cabinet ministers, the TEC, and VCs might like to pretend otherwise. If Labour isn’t prepared to fund the university adequately, then it should accept that it is leaving Otago’s senior leadership with no other responsible option than to add to its debt.

4) What kind of action do we need to take in order to build pressure on both the University’s senior leadership and the Labour Government?

Firstly, it is important to appreciate that this is not a done deal. It’s a proposed course of action. Whether it is implemented at all, and if so, to what extent, will depend crucially on how effective staff and students are in fighting for every job, every course, every programme, every minor, every major, every degree, and every diploma. We can fight, and if we stay strong and united, we can win. Court action by the TEU threw out AUT’s planned redundancies at the start of this year. At VUW the VC talked about job cuts all through COVID but could not follow through. A mass campaign led by the TEU at Victoria University successfully prevented the kind of redundancies being proposed at Otago.

Secondly, the fact that senior management has agreed to a joint approach to the Government for more funding is a positive step forward. The Government would be politically wise to provide a rescue package. Do Labour and the Greens really want the spectacle of proposed redundancies and a mass militant campaign opposing those redundancies playing out through an election year? It’s important to make it clear that there is going to be a heavy political cost for Labour if it continues to hammer the universities in the way that it has throughout its second term.

Thirdly, Otago has a proud history of militant mass protests against neoliberal tertiary education policies. It appears that Grant Robertson has forgotten the time when he was OUSA President and hundreds of students were occupying the Registry building to oppose rising fees, cuts to allowances, and rising student debt. We will remind him.

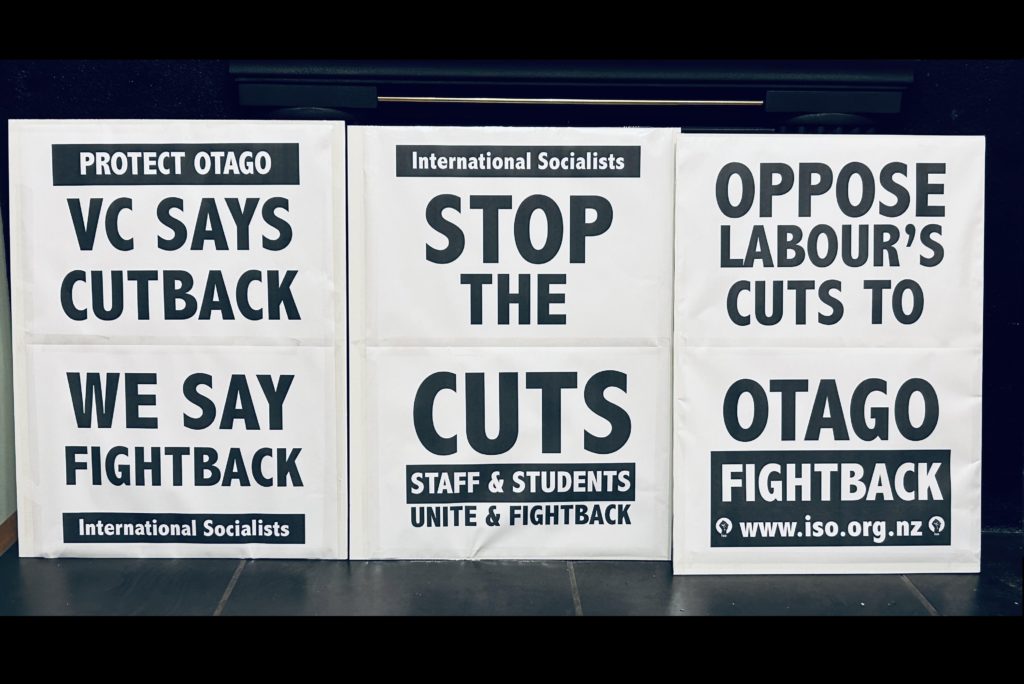

In building this campaign we will need big and small forms of resistance. Rallies and marches, pickets, speak outs, use of online and social media, educational events – spanning the entire university and reaching out to the people of Dunedin. We need to learn from the lessons of the past, from the successes of other campaigns, while thinking in smart, flexible, and innovative ways about how to build pressure on both senior management and the Government.

Finally, the University is, in effect, fundamentally altering our conditions of employment outside of the bargaining period which concluded only six months ago. Staff have a strong moral justification for taking various forms of industrial action, even if Section 86 of the Employment Relations Act is cited to scare staff into thinking that “strike action is not possible”. The reality is that if the action taken is large and successful the legal remedies available to the employer maybe not be as viable as they think, and of little aid in winning the battle of ideas pertaining to this issue.

Protect Otago! Save our university! Staff and students – unite and fightback! We are many, they are few!

References

MoE, (2017). Profiles and Trend 2016: New Zealand’s Annual Tertiary Education Enrolments. Wellington.

MoE, (2019). Export Education Levy Annual Report for the Year Ended 30 June 2019. Wellington.

Roper, B. (2018a). ‘Neoliberalism’s War on New Zealand’s Universities.’ In New Zealand Sociology 33(2): 9-39. Available at: https://search.informit.org/toc/nzs/33/2

Roper, B. (2018b) Neoliberalism’s War on New Zealand’s Universities – Supplementary Notes.’ Available at: Brian S Roper’s Blog. http://briansroper.blogspot.com/2018/09/neoliberalisms-war-on-new-zealands.html