The below is a transcript of a talk given by the ISO as part of Dunedin Pride Month, sharing the radical history of queer liberation in Aotearoa.

A couple of notes at the front: Firstly, we’ll be using the phrases queer and takatāpui as umbrellas for the rainbow community. We acknowledge that that the word queer is not universally embraced across the community, but we use it here in the spirit of a successfully reclaimed slur. And secondly, we want to acknowledge that while this talk is predominantly focused on post-colonial history, queer life did not begin with colonisation. The fact that we know relatively little about pre-colonial queer relations is one symptom of the vast cultural genocide visited on this whenua by colonisers.

But we do know that as long as people have walked this land, queer people have been here. A tale handed down through Māori oral tradition tells the story of Hinemoa who dressed as a man to seduce Tūtanekai, though this man’s heart belonged to Tiki, whom he called “taku hoa takatāpui” – my intimate, same-sex friend. This story traces its roots to sometime in the 1300s.

Such accounts and stories of takatāpui relations and indigenous genders are buried but not all lost. Researching and uncovering these taonga is one underappreciated facet in today’s struggle for a stronger, queerer future.

Eventually the colonial invasion of Aotearoa by Britain led to the use of British laws and societal expectations surrounding homosexuality and gender expression, which clashed greatly with any takatāpui relations and indigenous genders already present. For those who know their history of this country, you know that the New Zealand Police grew from what was known as the Armed Constabulary, a so-called “peacekeeping” militia that went on to engage in and enforce the theft of Māori land for the Colony of New Zealand. Given what we know about the violence and slavery enacted on Māori communities by the Armed Constabulary, we can imagine how colonial “peacekeeping” forces may have handled displays of queer activity by the indigenous Māori.

As a Crown colony and eventually a Dominion, British law regarding homosexuality was more or less copy/pasted into New Zeland. That is to say: “no gays allowed”. As New Zealand began to rapidly expand due to the Gold Rush and burgeoning urban centres, the Armed Constabulary and subsequent Police Force policed homosexuality as they did other crimes, in keeping with British, Irish and Australian standards. Consequences ranged from medical and psychiatric referral, through to various forms of torture – though of course in the 1800s and most of the 1900s, these were effectively the same thing.

The attitude of the Government towards gays was not lightened by World War One. In fact, the rising nationalist sentiments and drive towards the “moral status” of the ANZAC war effort worsened the prevailing bigotry. However, queer life did enjoy a small flourishing across the world in wartime. The confluence of men in the military, and resulting convergence of women now in workplaces triggered a rise in homosexual activity. Evidently, the world was not as heterosexual as it was pretending to be.

Attitudes begun to change after the war, queerness, including asexuality, became medicalised and viewed as a mental defect. The government employed methods designed to, in heavy quote marks, “cure” what they saw as sexual deviants. These conversion therapies ranged from deeply flawed psychiatry to outright torture methods.

Despite this intense oppression, queer people found ways to connect through underground networks, and they facilitated meetings and discussion amongst their peers. These spaces were also used for casual sex, however this was a dangerous escapade, as New Zealand law enforcement was seeking them out to incarcerate them.

Moving on to World War II, we see a repeat of the conditions of World War One – men in battlefields, women outside the home. Again, this made gay existence slightly easier even under wartime conditions.

That said, the New Zealand government still considered homosexuality a mental disease, and men who were dishonorably discharged from the military due to gay activity were imprisoned, and these records weren’t expunged after the homosexual law reforms came in, because there was no retroactive enactment of those laws.

During the 50s, a time of great civic growth for New Zealand, the gay scene once again grew a little.

People had to be discreet but covertly gay coffee houses and bars, and lesbian and gay lifestyles were becoming more public, despite repression at the hands of the law.

After the 50s, the gay liberation journey really starts to kick off. During the 60s, as the gay liberation movement took off with USA/Britain, public opinion on the gays did not change too heavily, though polarisation became to emerge. This is something that we see emerge in any liberation movement. As an oppressed identity begins to build a movement for liberation, progressives rally to their cause, while reactionaries feel that something is being taken from them, and thrash against the threat of modernity.

Efforts were being made underground by secret organisations to try to develop legal precedent for homosexuals not to be discriminated against due to being out and proud. Such attempts were unsuccessful, but did lead to networks of resistance beginning to form.

Throughout this history, there is little to no sign of what we could label a “social movement”. There are gay scenes, for sure. We’ve had gay scenes in one sense or another since the 40’s, maybe earlier. It wasn’t until the end of the 60’s and start of the 70’s that we say the gay liberation movement begin to take form.

Underground organising and discontent within the gay community had been simmering for a long time, and the uprisings of queer radicals in Britain and the US were beginning to provide a defiant optimism here. Conditions were ripe for a sea change, but as some old Russian dude said, sometimes history needs a push.

History was pushed on March 15, 1972, after a young Māori woman had her visa to study gay power in the US rejected by a consul who called her a sexual deviant, to her face. At a student forum of the University of Auckland, proud, open lesbian Ngāhuia Te Awekōtuku yelled to the gathered students: “Who out there is crazy enough to come and do this with me? Let’s start gay liberation!”

Within only a week, the Gay Liberation Front was founded, ready to channel the community’s latent gay power into radical action.

This grassroots organising would result in a number of bills going before the government on abandoning the criminalisation of homosexuality. However most of these bills were highly unpopular with the then current government and were often subjected to moral panics which lessened political motivation in pushing for the decriminalization of homosexuality in Aotearoa during the 70’s and most of the 80’s. Meanwhile, British laws against homosexuality (which had informed our own) were changing for the better in Britian, first for England and Wales in 1967 and again in the early 80’s for Scotland and Northern Ireland.

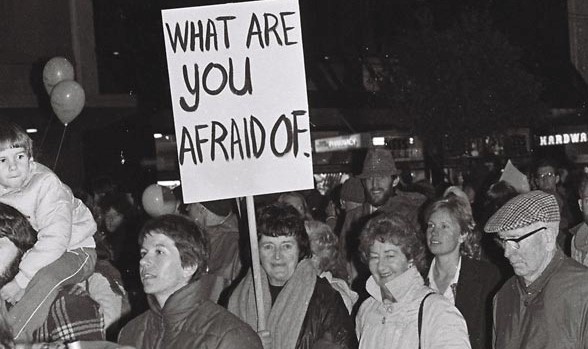

Thus radical action and public information campaigns were thought most effective to both show that gay, lesbian and bisexual people were not alone as well as inform the heterosexual public. Examples of this can be seen in the pride marches and other gay gatherings that pre-figured the “Big Gay Out” and similar events of today. These were often focused in large cities such as Auckland, Christchurch and Wellington for maximum exposure and range.

The radical gay liberation scene started to import disruptive tactics from the USA, such as “Zaps”, guerilla political theatre that saw activists dressing up as characters such as Batman & Robin and playing out a court of law scene, while Santa Claus chanted “ho ho homosexual, sodomy laws are innefectual!”

Other tactics included simply holding hands, or kissing in public, tactics that frankly might make some queer couples nervous today, but were wildly radical and head-turning at the time. And not just that – these tactics were genuinely dangerous. To stand up for gay rights was to put yourself at risk of verbal and physical abuse.

Unfortunately, the original formation of the Gay Liberation Front founded by Ngāhuia Te Awekōtuku would not continue for all of the struggle for queer liberation in Aotearoa, as it fell to similar problems of internal racism and sexism which also plagued other Gay Liberation Fronts in America and Europe.

So being openly gay throughout the 70’s and 80’s was certainly not safe, particularly for gay men who were seen as acceptable targets of the homophobic. But the New Zealand public was losing any ability to turn a blind eye and pretend the fearsome gays did not exist. Queer people were coming out of the closet at an increasing rate, but hate attacks were prevalent, and people were still jailed for homosexual acts.

Much like in other parts of the words, the New Zealand radical left through the 70’s and 80’s held a handful of different positions towards gay liberation. The Stalinist and Maoist elements tended to follow the contemporary political lines of the Soviet and Chinese states – which is to say, they were often dismissive, at best, of the gay liberation movement. Other radical elements such as indigenous rights activists, anarchists and Trotskyists across the socialist spectrum put forth analyses that placed them squarely in the fight for gay liberation, as well as black liberation and women’s liberation, almost always opposing the more conservative “equality” and “assimilation” elements.

This is important to remember today, as this history is so often whitewashed as a sort of liberalism where society just had to convince enough people to give them rights, then they could have sex in peace and become out and proud while taking their place in the professional managerial class, managing an accounting department or whatever. No, the law reform was the end point of this journey, a journey that involved street confrontations, socialist organisations forming coalitions, exposing cops for their 2am intrusions and degrading physical examinations on gay couples, and so on. Today in this country homophobes might be falling to a minority, but if we had to convince a majority that we were worthy to exist, homosexual law reform would have been a much longer journey.

At a 1974 Gay Liberation Conference, Gay Liberation leader and member of the Socialist Action League, the late Dick Morrison put this statement forth: “All of these [anti-gay] laws have been set up for a definite purpose: to maintain the hetero-sexual nuclear family unit which present society depends on. People must be forced into definite sex roles to maintain it. “The law is oppression codified and enshrined” and of course it reinforces peoples’ prejudices: “well, if it’s against the law, it must be wrong!””

In 1985 and 1986 the bill which would become the Homosexual Law Reform Bill, went through the an exhaustive 14 months of investigation and readings, during which time anti reform protests formed outside of parliament to try and hold back its success. However on 9th of July 1986 parliament finally voted on it. And it just barely passed with 49 votes in favor and 44 in opposition.

However there were several shortcomings of this bill, such as the fact that it was not retroactive, meaning that men who had severed time in prison or had been arrested for homosexual actions would need to carry out their sentences and still carry records of them being arrested for something that was no longer illegal. Essentially, still facing punishment for their existing while gay.

Another issue here was that gay and lesbian people were not given protection under New Zealand Human Rights Bill, thus making it legal to discriminate against openly gay and lesbian peoples in Aotearoa until 1993 when the new New Zealand Human Rights Act was passed and discrimination against gay and lesbian people in Aotearoa was made illegal.

These were major turning points. Of course, legislative change does not eliminate all structural barriers to freedom, but given that the unengaged masses look to parliament and the law as our central political structures, removing homophobic legislation will affect public perception of queerness for the better.

In 2004, we saw the Civil Unions Act passed into law. This separate but equal system for gay “union” as opposed to straight marriage was desperately weak, but given society’s dependence on the nuclear family, it was celebrated by some as an incremental step, a workaround to grant access to the benefits provided by legal marriage, while not having access to the institution itself.

In 2013, Parliament undertook a conscience vote on whether same-sex couples should be covered by marriage law. This passed 80-40.

We’d like to take a moment here to list the bigoted MPs who voted against the inclusion of queer people in marriage legislation, who are currently still in Parliament, so you know who has actively fought against our liberation.

From the Labour Party, two remain: Damien O’Connor and William Sio.

From National, David Bennett, Simon Bridges, Melissa Lee, Todd McClay, Mark Mitchell, Simon O’Connor, Louise Upston, and of course, Dunedin’s own Michael Woodhouse.

Of course it’s worth mentioning that access to such institutions as state-recongised union or marriage, and the manufactured good gay/bad gay dichotomy that has grown alongside this struggle, does not represent full liberation. Radicals within the queer community have long advocated for the abolition of the nuclear family unit as the default, societally subsidised paradigm. Not because, as the fearmongering right wing would suggest, that we want to tear society apart for fun, but because we should all have the freedom to pursue any form of consenting adult relationship that we please with one another, for as short or long as we please, without the state keeping record, and dishing out or taking away our social safety nets depending on our relationship paradigm.

Though language, understanding and expression has changed over time, transgender people have always been present within strong queer liberation struggles, though with unique struggles and oppressions, and oftentimes facing the same hateful divide and conquer tactics that plagued older liberation movements. Transgender liberation requires us not only to dismantle existing oppressions, such as legal bureaucracies and gender binary-based processes, but also to build structures and processes that enhance access to affirming healthcare. Doctors who actually know how this stuff works. Adequate scientific and sociological research as a founding for that knowledge. Access to hormones and self-ID documentation without medical professionals holding up hoops to jump through.

Though it might feel hopeless at times, this is a movement with momentum, and a struggle that we are winning. We are making advances and we’ll make more. I won’t give the so-called “feminist” TERFs airtime that they don’t deserve, but suffice to say, their recycled homophobia has no foothold in the face of queer defiance.

We still have a lot of work to do, particularly on the fronts of transgender and intersex liberation, on migrant exploitation, and on the economic and property relations that underpin the exploitation of the working class. History teaches us that what is seen as radical today can be accepted if we fight to change the conditions we are immersed in. I’m going to read to you a small piece written by gay socialist Bill Logan, one of the leaders within the Gay Liberation Front who fought for and won Homosexual Law Reform, to illustrate that true liberation is a struggle, and will not happen without us.

This was written in the mid-90s about homosexual law reform, but his observations find a chilling echo in our struggle for transgender liberation today.

“It was sixteen months of hard, intensely stimulating work, physical and nervous exhaustion, and a certain amount of pure terror. The vote in Parliament at the end was finely balanced, but it was a victory, and as happy an ending as you get in real life.

But there were casualties along the way. Homosexuality was the subject of intense debate and social polarisation, and bigotry got more violent than usual. Two people I knew had their lives destroyed by severe head injuries. Sometimes you wondered if it was worth it.

Every teenager in New Zealand who was worried about his or her own sexuality, particularly every teenage gay male, knew that this was a debate about whether he had any worth as a human being. There were more gay-related suicides than usual. And we went on, presenting our side, pretending to be calm and rational.

The debate brought about a change in the law, and a change in perceptions, and it’s now easier to be gay or lesbian than it was. Much easier. So it wasn’t a mistake.

But in most ordinary, nice families in New Zealand there is still an undercurrent of homophobia, and the high schools remain poisonous places for young people with uncertainties about their sexual orientation, or with certainties which don’t conform. New Zealand still has perhaps the highest youth suicide rate in the world, and sexual orientation contributes hugely to that figure.

It’s easier than it was, but it’s no rose garden.”

Bill is still fighting the good fight, as a revolutionary socialist.

The opposition between conservative assimilationist queers and radical liberationist queers exists to this day. Assimilationist queers often find themselves as tokens in businesses or organisation which pinkwash the bigotry of power and capital. The Rainbow Tick hands out its certifications for money, but does nothing when transgender workers are bullied out of Rainbow Tick-Certified workplaces. Cops try to attend Pride marches en masse, in uniform, and assimilationist queers defend the state as it uses queer lives and spaces to pinkwash itself, while radical liberationist queers, such as those now active in People Against From Aotearoa, use this faultline to fight against structural oppressions against Māori and queer, especially trans people.

So, what is our place in radical queer struggle today? Obviously, combatting those oppressions above, and articulating how the liberation of indigenous people, of women, of queer people, of migrants, are all bound up in each other’s struggles. When we look to the rising tide of transphobic hate in the UK, the subsequent absolute erasure of intersex bodies and lives, and reactionary anti-gay laws being drafted and enacted in the US, we’re unfortunately reminded that the gains we have won need to be protected whenever they’re challenged. The international far right is increasingly trying to paint over liberationist victories as merely another facet of the “culture war”.

The best thing that we can do right now to fight back, is to organise. Get involved in progressive or queer community groups. Join your trade unions to empower protections for queer workers. Talk openly to each other about the issues the rainbow community faces. Find and seek out organisations that match your politics. Here in the International Socialist Organisation, we’ve had the networks in place to quickly respond to the need for demonstrations in favour of law reform, and against the will of reactionary TERFs who fight those reforms. We’ve held educational meetings to provide each other with the tools to develop cohesive arguments for queer liberation. We lodge submissions to improve legislation that can chip away at institutional roadblocks.

We should all remember to look at this struggle from a wider angle, and see how it has shifted over the last century. Bigots have always been there, and queer endurance and defiance refuses to lose, because for us, this is not academic. We aren’t fuelled by hate and bigotry – this is about who we are, and this is about defending our community and building a world that will be safer and more vibrant for those who come after us.

Our liberation comes from radical action, not apathy nor idealism. Our liberation comes from altering the material conditions of our society, and the ideological and legal superstructures that grow from it. Our liberation comes from a vision of a future where we are free from systemic oppression, free from toiling for the bank account of private business owners, free from pinkwashing capitalism and imperialism. We have our comfort to lose, but a world to win.