Strike statistics are useful for assessing the state of workers’ militancy. Fortunately section 98 of the Employment Relations Act requires information to be submitted to the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE) after every strike or lockout. This source provides statistics up to and including 2017. For this year, so far, we must rely on media reports. In the last issue of Socialist Review we cited several strikes and gave our assessment that we are witnessing a revival in class struggle. We now provide more in-depth information.

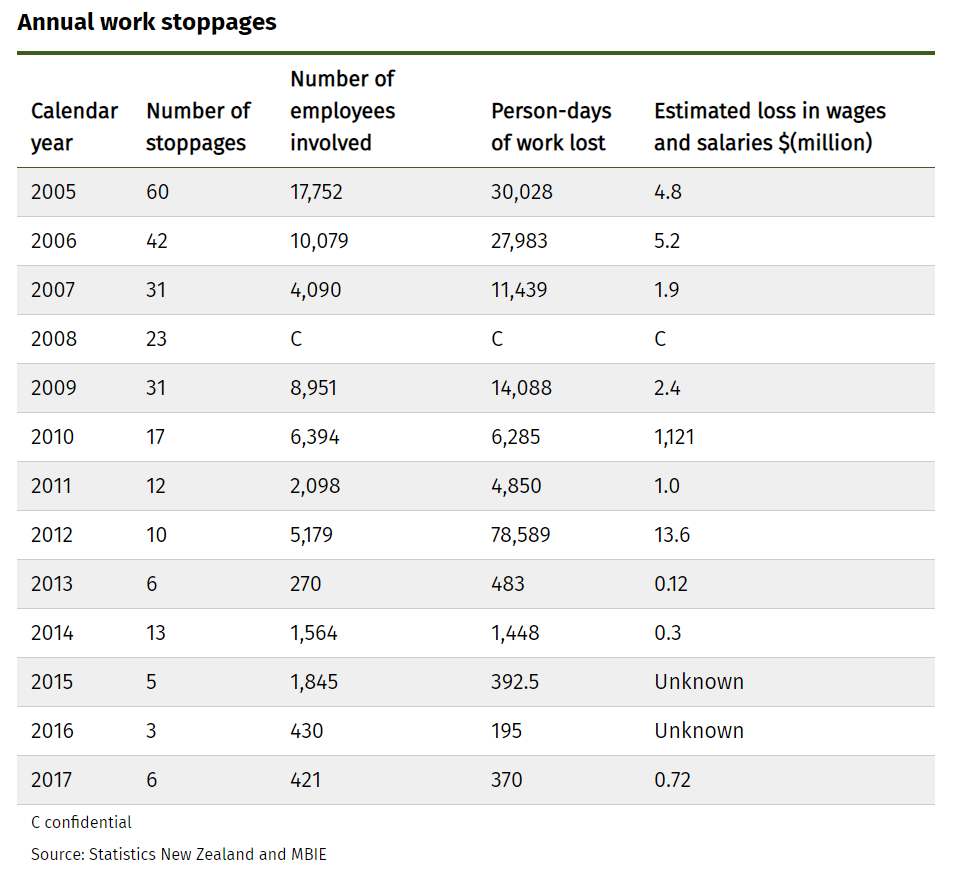

Table 1 shows the decline in industrial action since 2005, in which year there were 60 work stoppages involving 17,752 workers. From 2013 to 2017 the New Zealand working class hit rock bottom. In 2016 there were two strikes and one partial strike involving a total of just 430 workers. A partial strike is defined by law as any industrial action short of an actual strike. 2017 was hardly better with 6 full strikes by a total of a mere 421 employees.

2018 marks a complete break with the downward trend. National public sector strikes this winter by health workers, primary teachers, Ministry of Education learning support specialists, Inland Revenue staff, MBIE staff and Ministry of Justice staff have involved over 60,000 workers. By the end of the year this figure may well have risen considerably. There has not been as many workers involved in action during a single year since 1991 when there was an upsurge in strikes against the enactment of the Employment Contracts Act. Regrettably, at that time the Council of Trade Unions refused the clamour for a general strike that may have forced the National government to withdraw the anti-union legislation. Since this article was first compiled there has been the bus strike in Wellington and there will be another round of NZEI strike action. The revival is a fact.

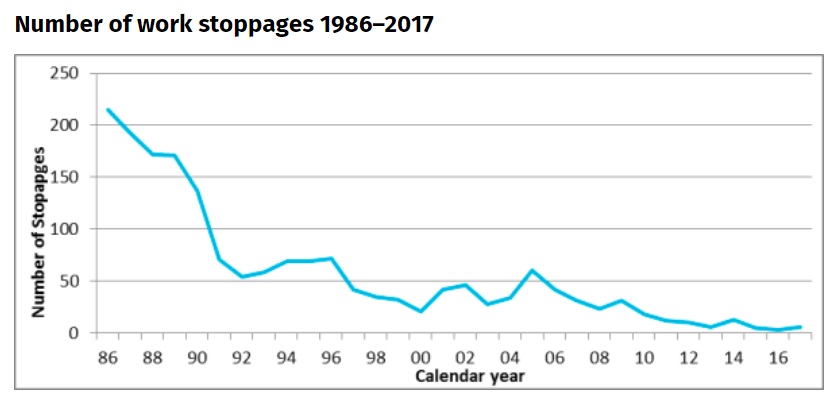

Media attention has concentrated on the nationwide public sector strikes, but there has also been a significant number of strikes in the private sector. It is the number of strikes that is the best indicator of how widespread the mood for action has been. Table 2 shows the longer-term trend of decline since the mid-1980 until this year.

At the rate we have seen so far this year, the number of strikes in 2018 will be back to the range seen in the mid-2000s, although perhaps the number will not reach the 2005 peak of 60 stoppages.

Table 3 has been composed by gleanings from the media. It may well under-report stoppages and may not be accurate in every particular. However, it serves the purpose of providing a guide to the number and diversity of strikes to September this year.

This year’s nationwide public sector strikes have exhibited a great deal of enthusiasm by the participants, many of whom had never been on strike before. They have been brief affairs ranging from two to twenty-four hours. A 2-hour strike by court workers has been supplemented by a work-to-rule. These actions have been what might be called demonstration strikes, whose purpose is to show the strength of feeling in the workforce in order to prompt the employer to grant concessions. Union bureaucracies have been firmly in control of the industrial action strategies.

In the private sector strikes have been more varied in their character, but they too have mostly been limited to just hours or a day. Some, however, have been more hard-fought. For example, about 20 First Union members at Atlas Quarry commenced action on 2 August. The company responded with a lockout notice; but the workers stuck it out and on 14 August won a deal that gave them good improvements on pay and conditions. One of the strikers is reported as saying “We stuck together and were in it for the long haul.” The battle at Chep in Christchurch has also been tough. The workers there have taken several rounds of action. At both Atlas Quarry and Chep a feature has been the donations and food parcels from the local community. Indeed, generally speaking, strikes have public support.

A characteristic of the strikes this year is that they have been offensive: they have been for improvements. This has not been the case in recent years when in the few strikes that did take place were often defensive; to stop things becoming worse. This review of industrial action shows that there has been a general rise in workers’ confidence to fight and win concessions. In the public sector pay equity and staffing levels have been key issues. In the private sector battles have been over low pay, but not exclusively very low pay. At Pacific Steel and OceanaGold, for example, the E tū union cites record company profits as reasons for general pay improvements.

Without doubt 2018 is a turning point in the class struggle. The contrast with the last decade is stark. A sense of proportion is needed though. This is not a huge strike wave by any means. Tens of thousands are not yet flocking into union membership. The action has been in the pre-existing unionised sectors. The vast majority of workers outside the public sector are still unorganised. Starting from a low base, the revival in industrial action has potential to go a lot further.