The politics of “law and order” in New Zealand finds its natural home in the current pro-business coalition government. It is no accident that a central focus on accumulation is complemented by a “tough on crime” approach: there has to be some way of managing the fallout, the communities abandoned by austerity, those who don’t fit neatly into a profit matrix – some way of justifying the violence visited on them.

True to form, the National-ACT-NZ First coalition has introduced a raft of crime legislation since coming to power. This includes a reheated boot camp for youth offenders, reinstated “three strikes” legislation, a ban on gang patches, a total ban on prisoners voting in general elections, and sentencing reforms which promote longer sentences.

Throughout this process, National has repeatedly ignored evidence from legal experts and advice from their officials. They even admitted, back in 1997, that boot camps do nothing to meaningfully reduce youth re-offending. Every bit of information since then indicates they were right.

What will almost definitely happen, however, is a huge expansion of the prison population over the next decade; a population who will be disenfranchised, double-bunked, and spend far more time behind bars.

This affects all of us. The more the law comes to mean punishment and control, the more it encroaches on our participation and self-determination. “Law and order” legislation must be opposed wholesale.

But how, and where, should socialists intervene?

So-called “law and order”

A closer look at the phrase “law and order” reveals a series of problems.

On the surface, the “law” part refers to a set of rules, and “order” refers to the harmony they produce. But only certain parts of the law are being implied here. Who, hearing the phrase “law and order”, takes it to mean zoning restrictions and business transactions? In effect, this arrangement empties whole sections of the law – public policy, taxation, environment, employment, property, commerce, competition – and reduces it to the criminal aspect.

Folding these other areas back in exposes the contradictions of the coalition’s project. While firming up the punitive sections, it moves to loosen, obstruct, and bypass many other parts of the law. During their first year in office, the coalition introduced sweeping deregulation measures – scrapping Fair Pay Agreements, the Māori Health Authority, the Clean Vehicle Discount Scheme, forestry registration systems, and established fast-track consenting for infrastructure and development projects. They have drastically reduced the flow of resources to the public sector, whose job it is to develop and maintain law in the first place – nearly ten thousand public sector jobs have now been cut. Furthermore, they have passed a record number of laws under urgency, diminishing the power of the legislative branch in each case.

These actions remove some of the system’s few windows for democratic oversight, and surrender public territory to the unruly logic of profit-making. This approach to “law” is a direct upsetting of the “order” supposedly being offered. As the NZ Crime and Victims Survey reported last year, an increase in violent crime victims between July 2023 and June 2024 “is likely due to rising economic pressure experienced by many New Zealanders”.

This raises another contradiction. Since at least the 1980s National has positioned its “law and order” policy around protecting the victims of crime. None of the major parties, however, are interested in preventing crime.

To understand why crime happens, we simply need to look at the statistics. Within the last decade, according to the Ministry of Justice, around 77 percent of prisoners have been victims of violence, up to 87 percent were unemployed before sentencing, over 52 percent are Māori (despite Māori making up around 17 percent of the general population), and 91 percent have been diagnosed with either a substance use or a mental health disorder during their lifetime. As well as reflecting well-established biases in policing and sentencing, these statistics clearly reflect the legacy of colonialism, poverty, and dispossession.

Harm continues to circulate through society because harsher sentencing and increased policing do not address these problems. In many ways they make them worse by concentrating violence into one area, and removing prisoners from their communities and networks of support – often leaving them more alienated and impoverished than before.

So much for the victims, then, who are no better off under these arrangements. We might also notice that the word “victim” has been captured, cutting off all those prisoners who have been victims of violence, and all those who suffer now from living in cramped, dreadful cells. This helps no one – even those living outside the bars – because it raises the requirements of victimhood to the level of innocence: a sometimes-impossible, always alterable threshold. Obeying the law becomes the condition for being considered fully human and deserving of rights, even if that law is nonsensical or unjust.

Here we get to the heart of the matter: National smooths over its contradictions by collapsing one meaning of order: “a harmonious arrangement” into another: “a command to be obeyed”. Put another way, The Law is something the people should follow, not create.

How we got here

That we are seeing a coercive turn at this current moment should not be surprising. Historically, police and prisons have always expanded as class antagonisms become sharper. The prison boom in the 1980s – both here and abroad – came at the exact time the welfare state was being dismantled and the manufacturing base shifted overseas.

Since capitalism has no mechanism to solve these crises, it employs a spatial fix: displacing the visible effects of a problem to another location. With prisons, the state no longer has to address the worst parts of racial inequality, poverty, and unemployment. It can simply gather them into certain areas.

Now that we are again facing a global economic slump, the batons are coming out. It pays to keep this in mind against the slew of arguments from legal and bureaucratic centres, that change within the law is the only sensible option and those fighting against or outside the law simply need to grow up and learn that it’s never going to happen. They’ve got it backwards. The legal system requires capital in order to function. Without the producers, there would be no bricks for courtrooms and no money for police – in other words, it is essentially held captive by the business class.

This is abundantly clear in the gulf between “legitimate” and “illegal” acts recognised by the law. It is illegal to steal bread if you are starving, or to blockade a coal mine. But it is totally legal to operate a coal mine during a global warming crisis. And it is not punishable, apparently, to invade Iraq and kill over a million people.

The revolutionary Rosa Luxemburg summed up the absurdity of the problem like this:

What is actually the whole function of bourgeois legality? If one “free citizen” is taken by another against his will and confined in close and uncomfortable quarters for a while, everyone realises immediately that an act of violence has been committed. However, as soon as the process takes place in accordance with the book known as the penal code, and the quarters in question are in prison, then the whole affair immediately becomes peaceable and legal. If one man is compelled by another to kill his fellow men, then that is obviously an act of violence. However, as soon as the process is called “military service,” the good citizen is consoled with the idea that everything is perfectly legal and in order (Gesammelte Werke III).

The state does not execute some abstract idea of “justice”. Rather, our common idea of “justice” has been shaped – and subverted – by the state.

As lawyer and activist Moana Jackson used to point out, the coercive state has been so normalised that we forget it’s still relatively new. For the vast majority of Aotearoa’s history, police and prisons never existed. As Jackson explained in a 2017 speech, “Why did Māori never have prisons?”, there were other ways of dealing with harm closer to restorative justice.

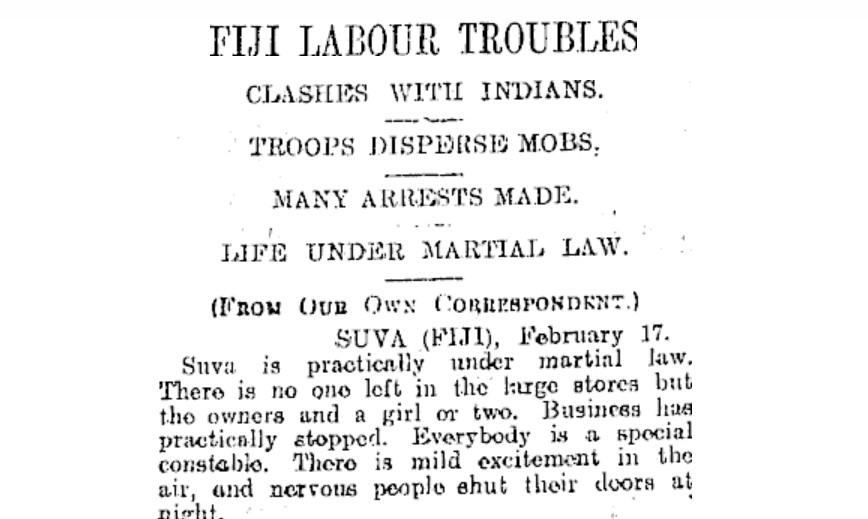

When these punitive measures did arrive, they were explicitly for acquiring land and repressing anti-colonial resistance. In the 1840s Governor Grey established the Armed Police Force as paramilitaries to surveil and terrorise areas outside European control, and laws soon emerged to support these actions. By 1863 the Crown passed the Suppression of Rebellion Act, which authorised the Governor to “punish all persons acting, aiding, or in any manner assisting in the said Rebellion”, either by death, penal servitude, or detainment. That same year, the New Zealand Settlements Act allowed the Crown to confiscate all land, without compensation, from those same groups deemed “in rebellion”.

As the more recent events of Bastion Point, Ihumātao, and Operation 8 demonstrate, the basic purpose remains: the police are here to protect accumulation (including land), especially during moments of crisis and rebellion.

Fighting back

For socialists, the state does not represent a legitimate power. It embodies, instead, a racist institution that perpetuates injustice. The sooner everyone rejects its authority, the sooner we can go about liberation. As Martin Luther King Jr. wrote from his cell in Birmingham Jail, we all have “a moral responsibility” to disobey unjust laws.

Some of the most inspiring social movements in our history have come when we collectively decided to reject bad laws, such as openly defying conscription 1917 and 1972, or refusing to pay the newly-introduced hospital bills throughout the 1990s.

Working class confidence grows leaps and bounds in these moments, when you realise your small protest gathering can break through police lines, or occupy a street without warning. The tide shifts in one stunning moment and the law, usually omnipotent, briefly loses its power.

This past year has brought a few such brilliant cracks in the state’s authority: of course, Hana Rawhiti Maipi-Clarke’s fantastic haka in Parliament; the People’s Committee hearings against the Regulatory Standards Bill; and, overseas, the wave of support for Palestine Action.

There are resources for hope to be found here. The state’s legitimacy rests on the will of the people, and we can take it away if we choose.