The ABCs of Socialism is a series of short articles on key socialist concepts.

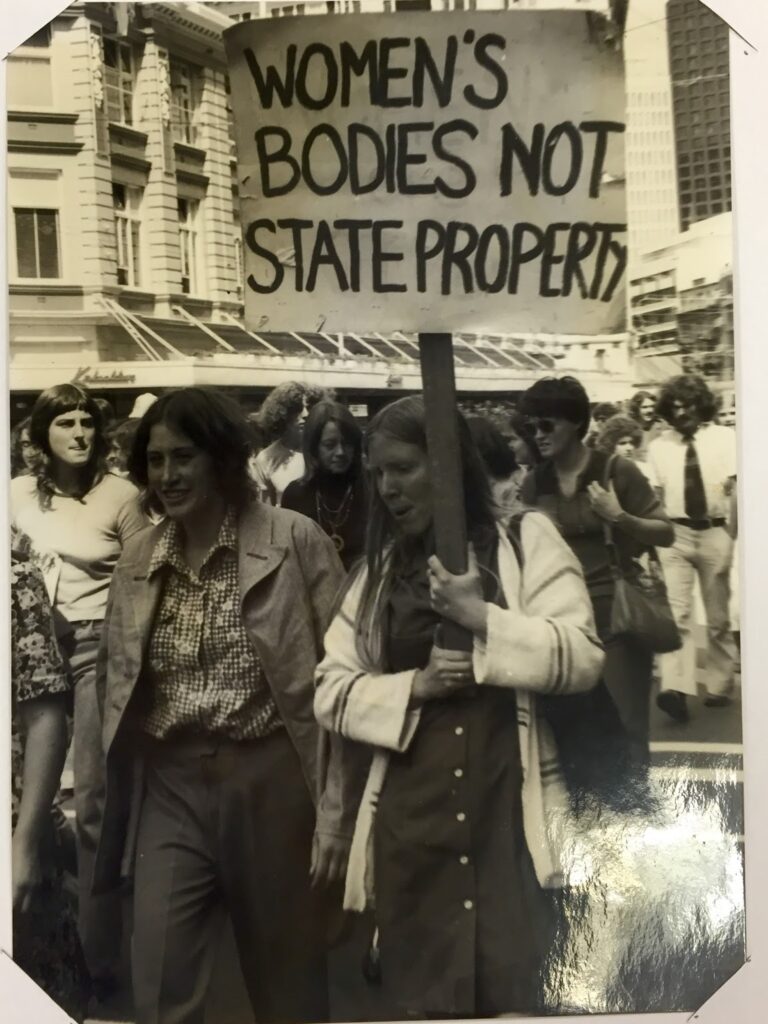

Women are grossly exploited under capitalism. Central to this is the burden of the double shift – the shift at work in which women are paid their wages, and the unpaid domestic work and childcare that women and other marginalised groups have borne disproportionately as a free service for the state and economy. The fight for women’s liberation and equal rights has traversed centuries and has won significant victories, which should not be understated. However, especially in times of crisis under capitalism, women’s bodies and livelihoods are put in jeopardy. This is conspicuous in decision-making in New Zealand as part of the wider international capitalist agenda. Evidence of this is in the overturning of abortion rights in the US, the relentless attacks on trans rights, and the New Zealand coalition governments’ extensive cuts to public services that have further harmed especially marginalised and gendered strata within the working class. All have had devastating impacts on women. The never-ending struggle for oppressed groups to gain and regain rights is a testament to how true liberation cannot be achieved under capitalism.

Marxist analysis understands women’s oppression as structural, with economic, historical, and psychological factors all reinforcing each other. As socialist writer and activist Jean Tepperman writes:

Early experiences in infancy and childhood shape the very core of our personalities according to certain conceptions of what it means to be female or male. The kinds of work expected from men and women differ greatly in a sexual division of labor affecting every area of life.

Under capitalism, women’s lives are shaped by the realities of reproduction and child-rearing, unpaid domestic work, wage labour, heterosexist socialisation, and sexual violence.

The shape of the family and domestic work has looked very different across history. In many pre-capitalist and indigenous societies, work such as caring for children and preparing food was done communally. The gendered division of this work has varied and certainly has not always conformed to what is presented as “traditional” now. In pre-colonial Māori society, for example, men played a very active role in nurturing children. The concept of “marriage” has also varied greatly. While strictly enforced monogamy (for women) became the norm for the capitalists and other ruling classes for purposes of inheritance, other societies have had different expectations around sex, procreation, and property.

The relationship between “public” and “private” has also varied. As Marxist writers such as Alexandra Kollontai and Angela Davis have noted, women in various pre-industrial societies created products in the home such as textiles that could be traded through the market. The shape of family life and domestic work all have implications for the position of women in society. In many pre-capitalist societies, lineage and inheritance were traced through the female line. Māori women had rights over land, often collectively, which they retained even after colonisation. Differing economic positions for women have meant different degrees of independence and freedom, and varying degrees of egalitarianism when it comes to gender roles in general.

Industrial capitalism transformed women’s domestic sphere. What was produced by the family or the commune was now produced on a mass scale by the industrial workforce. As Kollontai states, the family no longer produces; it only consumes. The capitalist nuclear family privatised domestic work – setting up the expectation that individualised families would shoulder most of the burden of looking after their members when they couldn’t afford to pay someone else to do it. Women’s domestic roles and duties faced a sharp turn in this process. Notions of the caring, nurturing, and supportive mother have been used as ways to justify women bearing extra burdens of housework and domestic duties that are not expected of men. The position of women under a wider class structure – and their unpaid domestic and childbearing roles – is necessary for the production of the workforce and therefore the economy. This unpaid domestic labour is a free service that women do for the benefit of the state and of bosses who benefit from the labour that maintains their workforces. Although this work is essential to society, housework is devalued as it does not directly create profit.

Marxist feminist, Nancy Fraser describes housework and social reproduction as, “important work in society, some aspects of which are very pleasurable and creative”. Through capitalist social and economic structures, this work becomes isolating, exhausting, and restrictive. As socialist writer, Barbara Ehrenreich writes on housework, “No one notices it until it isn’t done – we notice the unmade bed, not the scrubbed and polished floor”.

Although there have been movements lobbying for women to be paid for their domestic labour, that doesn’t eliminate the psychological burden and the isolated nature of housework in the nuclear family. It also does not necessarily give women opportunities for collective organising and industrial power. There is power in working-class struggle; in workers’ ability to produce or stop production. Marxist activist, Angela Davis writes, “As workers, as militant activists in the labor movement, women can generate the real power to fight the mainstay and beneficiary of sexism which is the monopoly capitalist system”.

Capitalism recognises housework as inferior to wage labour in that it doesn’t generate profit. The ideological consequences of this have been the stiffening notions of women’s inferiority. The undervaluing of women’s domestic work has also led women’s wage labour to be understood as inferior to men’s. Women face higher levels of unemployment and receive unequal pay. Even though it is illegal, women are still sometimes paid less for the same work as men. In other cases, whole industries are underpaid because the work is seen as feminine and the workforce is primarily female. In Aotearoa, the national gender pay gap (2024) is 8.2% between “men and women”. For wāhine Maori it’s 15% and for Pasifika women, it’s 17%. In a system that values profit over human beings, these statistics, however harrowing, are not unexpected.

Women’s liberation cannot be achieved without the radical transformation of the fundamental capitalist unit – the family. This structure is an important element of the capitalist economic system and the relations of production. In the family unit, women are perpetually responsible for domestic work, are expected to take on the responsibility of childcare, and are often forced to become economically dependent on men, even if they are also workers. Through the privatisation of property and the family’s function in controlling wealth, the nuclear family unit reproduces and sustains inequalities, to the benefit of the bourgeoisie (capitalist class) and the loss of the proletariat (working class). The family not only fulfills an economic and ideological function under capitalism but is also a central and real place of personal relations in people’s lives. The nuclear family model reproduces social values central to capitalism and relies on heterosexist gender socialisation to control women’s sexual behavior, to control our bodies.

Socialism allows us to conceptualise new and more creative ways of organising society. There are aims for housework to become socialised, for communal food preparation centers, and for more involved childcare centers to take the burden off women. This will transform the role of families in society. Social relations would also transform with the privatised transformed into the collective – the individual into the group. These are important processes that are crucial for women’s liberation.

Women hold power as workers in our ability to strike, halt production, protest, and be a part of the working class struggle. Understanding women’s oppression under capitalism in our responsibilities of reproduction, child-rearing, domestic work, and wage labour leads us to understand that no amount of equal pay reforms or moves for better working conditions will solve this oppression. We have seen this with our Governments’ endless rolling back of hard won reforms from the removal of the gender, sexuality, and relationship-based education guidelines, to the proposed members bill to remove requirements for public service employers and boards to promote diversity, equity, and inclusion. These decisions disproportionately affect women, people of colour, migrant communities, gender diverse folk and many other marginalised groups. Even once structural barriers are removed, sexism and its intersecting oppressions of racism and heterosexism will still need to be challenged. Socialism does not inherently equal liberation for women but it does create the necessary conditions for women’s liberation to finally be realised.