Obituaries for Dick Scott, who died on New Year’s Day, have emphasized his importance as a figure changing how New Zealand history was written about, taught, and imagined, especially by Pākehā. He deserves those accolades, but we should remember too that his early, pioneering histories were written as part of a project to change the world, not just to understand it differently. Scott’s radicalism was forged in the clashes and struggles around the Depression and its legacy, the Second World War and, most importantly, the post-war labour battles that came to a climax in the 1951 Watersiders’ Lockout and supporting strikes. He left the Communist Party in his late 20s, but his early formation in class struggle politics helped shape his attention to injustices done to Māori, the bloody history of colonialism in New Zealand and the Pacific, and his determination to write popular, accessible history.

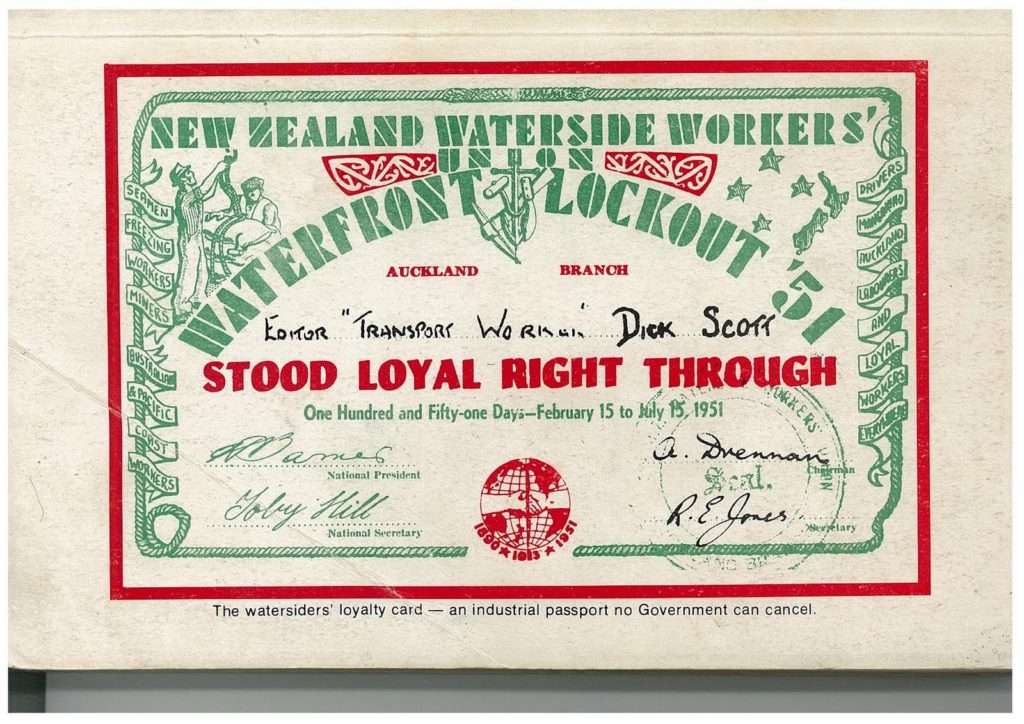

Scott’s two classics, 151 Days and Ask That Mountain, are essential reading for every socialist. The former told the story, in detail and for the first time, of the heroic Waterfront Workers’ Lockout in 1951, their battle against both a National Government determined to offer up the destruction of their militant, democratic union as a warning to other workers in Cold War New Zealand and the class-collaborationist politics of the trade union movement leadership. Scott was active in the Lockout as a journalist, reporter, inventor of solidarity schemes, and Communist activist. The watersiders recognized him as one of their own, and his account buzzes with the reality of the battle. The latter, a development of his 1950s work The Parihaka Story, told the story of the Crown’s attacks in Taranaki and the visionary resistance leadership of Te Whiti-o-Rongomai and Tohu Kākahi. Scott’s early interest on Parihaka grew out of anti-racist reporting he had done for the Communist Party, and appeared at a time when few Pākehā, even on the socialist left, were familiar with the details of this history.

Scott’s intellectual growth came through his contacts, both intellectual and activist, in the world of New Zealand Communism, in Modern Books, ‘the smart, virtually party-controlled bookshop and library in Manners Street’ and the ‘Unity Centre, the Communist Party’s district headquarters in Willis Street’ with its ‘workers’ lunchtime restaurant’ and ‘Mexican-Soviet hybrid’ murals. He was drawn to the Party looking for contact with organized labour and collective discipline when already a free-minded socialist, and left in the mid-1950s, before the great revelations of Kruschev’s ‘secret speech’ of the Soviet suppression of the Hungarian uprising. This helped kept him free from walking the long, boring road from left to right that so many ex-Communist writers, from the 1950s to today, have wandered down. It was the personal failings of the CP’s leadership, and their hypocrisies, that alienated him. Scott, writing in the early 2000s, took a balanced view of his years in the Stalinised Communist movement:

“But together with the traps of righteousness and rigidity, the self-deception, the refusal to face unwelcome facts, the ends and means rationalization, there had been rewards not to be discounted: I had learned to feel repugnance for racism, to wake up to the meaning of colonial rule, to believe in equality for women – even if practice at the domestic level was defective – and, short of an extended family, there had been introduction to a world of warm community, to a host of well-meaning people, the bulk of rank and file members.”

151 Days’s focus on workers’ self activity, and Ask That Mountain’s impassioned anti-racist, pro-Māori standpoint are products of this world, the best of the official Communist movement.

With Scott’s passing there is almost no one left from that world of 1940s and 1950s leftism and its huge battles. His anti-colonial and pro-worker books, the Radical Writer’s Life (2004) and Would a Good Man Die? (1993) as well as his better-known classics, are a fitting contribution to our unfinished movement for freedom.