The Tax Working Group, set up by the Labour-led government in 2018, has released its first volume of findings. This is where the government’s proposed capital gains tax is beginning to take shape, and a useful analysis underpinning the work of this group is important to understanding the broader political narratives arising from the working groups’ recommendations.

But first, what is a capital gains tax (CGT)?

Capital gains are the profits produced from selling an asset at a higher price than it was worth when it was first purchased. Thus a capital gains tax is levied on the value that was produced by doing nothing other than selling the asset when the time was right to make a profit.

Despite National’s hyperbole about the CGT being a ‘raid’ on landed wealth, the potential revenue of a capital gains tax has been estimated to be around $6 billion annually but it will take ten years to get to that level of return. Just under half of that revenue will be from residential investment, the rest will come from commercial, industrial or rural sales (which are typically much higher than residential sales).

Six billion dollars sounds a lot, but let’s put that in to perspective: last year’s tax revenue was $75.6 billion, which means if there was a fully established CGT collecting revenue today, it would only be increasing our tax revenue by about 7%. Not the kind of impact that the oppositions’ strong rhetoric suggests.

Furthermore, the capital gains tax rate on residential investments are only proposed at 25% according to the working group. This means someone who invested in a housing unit in Auckland a few years ago when the median price was around $700,000, could likely sell it for over $800,000 at the moment. On those precise figures, it would be a $100,000 profit, which is a very impressive appreciation on a small asset, but only $25,000 would end up in the government’s hands. A $75,000 profit for most families would put them on easy street, or well on the way towards a better family home. Hardly an attack on the “Kiwi way of life”. Workers, after all, pay tax on their income. How is it that those rich enough to buy extra properties pay none?

The truth is, of course, that it isn’t ordinary families that are making capital gains, and many families cannot afford to buy a house to own and live in let alone flip. The working group documents this unequal distribution of equity. Since we do not have a CGT in place to measure, the working group looked at who, in terms of wealth status, actually owns the assets that could be taxed for capital gains. It turns out that, on personal net worth, 70% of these assets are owned by the fattest 10% of wallets in the country! It won’t be ordinary ‘Kiwis’ living the so-called dream that will have to pay much of this tax, but the very wealthy who exploit ordinary people that will bear much of this burden. It is a burden that the very rich have earned by keeping wages low while letting rents and other living costs spiral upwards out of control.

The very wealth that enabled investment in residential property comes directly from the riches gained by reducing costs on everything, including labour.

Some of those who are rich enough to be making capital gains from very expensive assets are politicians themselves. We can’t know for sure just how much the ownership of these assets influences the decision making of politicians, but luckily for us we have Parliament’s Register of Pecuniary Interests (pecuniary: relating to money) and the politician’s own words to help us form some valid links between their economic status and their intended use of political power. This is what we mean when we talk about the ‘ruling class’ and their ruling ideas.

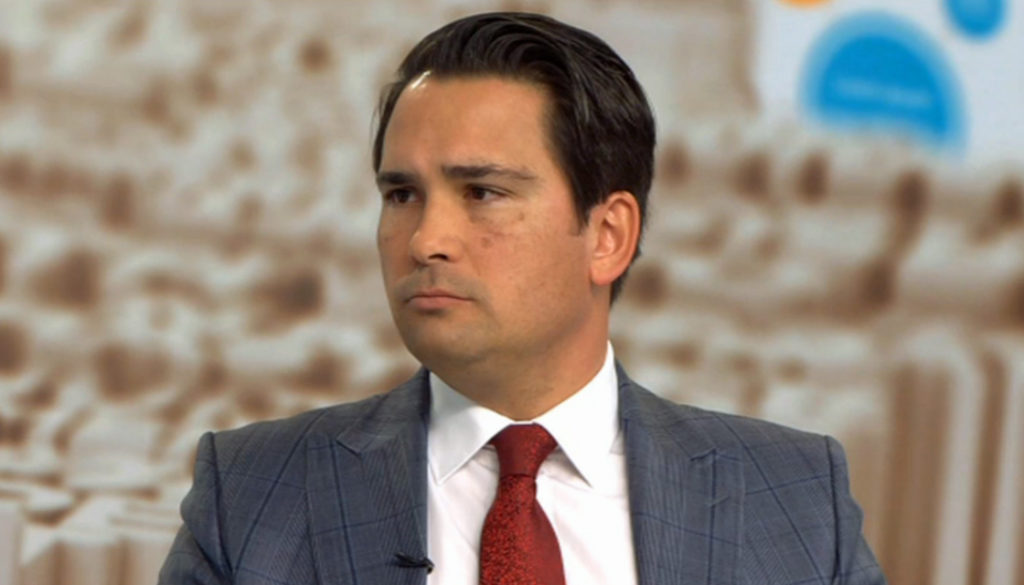

After National’s leader, Simon Bridges, failed at scaring ordinary workers into opposing a capital gains tax affecting New Zealand families, he is now saying that a CGT will cut KiwiSaver and other retirement savings. This is a man with very real worries; he has two retirement funds, but on top of this are his 3 residential properties in Auckland, Wellington and Tauranga. His fourth property is owned by a company he has shares in which … invests in property!

Former Speaker David Carter, has controlling interests in 11 rural industrial companies, as well as ownership of 2 rural properties and 2 residential, and has 2 retirement funds. As if he’ll need them! He is part of 3 trusts.

Nathan Guy, National’s agriculture spokesperson, labeled the CGT as a ‘raid on regional New Zealand’ to a meeting of ‘anxious’ farmers. The Register lists an impressive amount of wealth and property for this MP. He is the trustee and beneficiary of 7 personal trusts (and is trustee for one other) and has several properties, one of which is farmland.

Gareth Hughes, a Green MP, who famously called out Simon Bridges’ ‘kiwi dream’ dog whistle, has a family home, an ASB Kiwisaver and a mortgage. Judith Collins on the other hand, who attacked Hughes’s criticism, has a controlling interest in a hotel company, is a trustee/beneficiary of two trusts, and trustee to four more. She also owns two homes through superannuation schemes.

There’s much to be uncovered just by looking at these registers but what could be easily overlooked in the CGT tit-for-tat is their relationship to trusts. One could be forgiven for thinking that there are trust fund kids and some magical pool of money that keeps doling out to them. But trust funds don’t come from nowhere – they are safe havens for profits, that is, profits in the form of capital gains. The MPs may not have impressive amounts of properties, but the shocking amount of trusts they benefit from indicates that the very wealthy and those who aspire to be powerful, require returns from investments which are gains made from capital. This is how they get their income: by making money from money.

The Tax Working Group has uncovered the dirty truth about New Zealand’s economy: it’s a very thin layer of New Zealand who makes income like this.

It’s no surprise to us, however, that the eruption of debate and heavy rhetoric actually strengthens both major political positions. For Labour, despite its ill-advised Budget Responsibility Rules pledge, CGT makes Labour seem fiscally responsible to some of the business elite who worry that New Zealand’s financial situation after 9 years of National racking up the national debt (to reduce taxes on the rich) could put steady economic growth at risk. Thus finding untapped, sustainable revenue sources is a good thing for the economy. While at the same time, advocacy for a CGT shows Labour’s base that it is fighting for the ‘little people’. For National, they are doing the same thing but in reverse; they are fighting against the virtue-signalling do-gooders in Wellington, hand-wringing over fake poverty and inequality while ‘real’ kiwis are out working hard trying to build equity.

These are false positions but they are simultaneously major political positions. National is clearly a pro-capitalist party so they depend on a capacity for persuading workers and voters that inequality is just an outdated myth and making the rich pay for working-class luxuries is just not playing nice. When National is successful, the conservative layer of the ruling class can keep rough-riding everyone else. The fact is, inequality is growing and that’s because living costs are increasing (and increasingly paid to the private sector), while wages are being kept low (to keep private profits going up).

On the other hand Labour is trying to bolster its credentials with workers while simultaneously governing with the continued advice and consent of the business elite. The truth about Labour is that if they really cared about inequality, they wouldn’t be squabbling with big business over a meagre $6 billion tax. They should giving in to the demands of striking workers in the public sector! The very same workers who are doing Labour’s job of demanding more funding for their sectors. If they really cared about poverty caused by inequality, they should be increasing welfare payments and eliminating sanctions on the unemployed. Until they do, we must persist in our critical support for this Labour-led government. Income tax on the richest could be increased; Labour campaigned for this in 1999 and won. GST could be cut, or abolished. These would be genuinely redistributive reforms.

The ultra-wealthy don’t stand to lose very much from having a capital gains tax, but what they do stand to lose is some of the momentum that has sustained a 30-year long stretch of stealing from the working class that was legalised by both Labour and National governments. The working poor and unemployed aren’t in line to gain much from a CGT, though; like the nurses, teachers, midwives, justice workers and others, we will have to fight tooth and nail for the proceeds from this tax just as is the case for the proceeds of current taxation. The bright side, of course, is that tax brings such wealth out of the private trusts and puts it into the public coffers which places a larger share of the economic growth made from these islands and its peoples under more democratic control. The question then is what gets done with it. And that’s down to us, and to class struggle.