Remember, remember, the fifth of November, Gunpowder Treason and Plot. I see no reason why Gunpowder Treason should ever be forgot.

We all know these words. For centuries they’ve been handed down through the generations, first as a nursery rhyme sung by English children, and more recently popularised by the film ‘V for Vendetta’. David Lloyd, the artist behind the original graphic novel, has written that the Guy Fawkes mask his character wore has become “a common brand and a convenient placard to use in protest against tyranny”, and a quick glance around the world today reveals widespread use of it in everything from Anonymous to the Occupy movement.

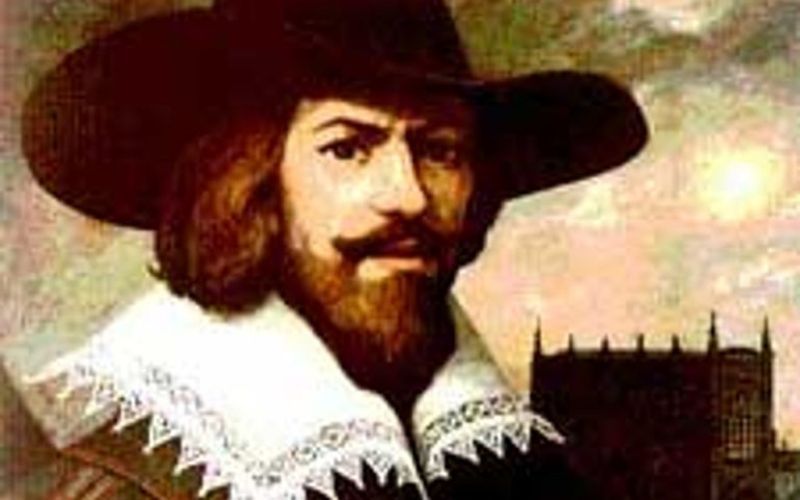

The tale of Guy Fawkes and his attempt to blow up Parliament remains an integral part of our culture, and one at times associated with revolution and social change… but has this always been the case? And do we truly remember all that we should about the fifth of November?

Powder and Papery

The story of the 1605 Gunpowder Plot itself is known to all, if only vaguely. A group of people opposed to the English monarchy of the time gathered together and hatched a plot to kill the King and his retinue. They obtained the lease to a room directly underneath the House of Lords and smuggled in barrels of gunpowder, but the conspiracy was discovered and the plotters who did not flee were executed.

So why did these people want to assassinate the King? At the time, Europe was torn apart by religious war. Catholic Spain had spent decades fighting a bloody war to keep the Protestant Netherlands under its control, and rival rulers used religion as a way to whip up popular sentiment against their imperial rivals. England, having broken with Rome under the rule of Henry VIII had a set of laws that discriminated against those would not join the Anglican Church, Catholics in particular. Theses ranged from fines and confiscation of property right up to capital punishment, and the Church hierarchy was driven underground.

When King James I took the throne, many Catholics hoped that he would usher in a period of moderation and religious tolerance. When this did not happen, and the King instead began to intensify anti-Catholic policies, attitudes towards him hardened.

Myth and reality

“More than four hundred years ago a great citizen wished to embed the fifth of November forever in our memory. His hope was to remind the world that fairness, justice, and freedom are more than words… they are perspectives.”

— V for Vendetta

This somewhat romantic interpretation of Guy Fawkes and his motivations has become widespread, and when people from Cairo to Oakland take to the streets wearing his face it is bound to be something along these lines that motivates them. The question is, what motivated the real Guy Fawkes? What kind of freedom was he fighting for?

Whatever the Wachowski Brothers might claim, Guy Fawkes was certainly no democrat. This was before the age of the French and American Revolutions, the Age of Enlightenment and the fall of the European dynasties. Fawkes and his co-conspirators aimed to kidnap the nine year old Princess Elizabeth and install her on the throne as a Catholic Queen, ruling on her behalf until she came of age and aligning England with Spain and Rome in the wars sweeping Europe. Prior to the plot, he had spent years in the Netherlands fighting to suppress an uprising against Spanish rule, and proved more successful at crushing revolts than starting them. It is probable that had the plot succeeded there would have been just as much religious persecution in England, if not more, the only difference being a change of target from the Church of Rome to the Protestants. Hardly freedom and fairness! Guy Fawkes would be bewildered by the causes his myth is now attached to.

Equally perplexed would be the ordinary people of England through the centuries, who celebrated this night long before us. To them, remembering the fifth of November had nothing to do with honouring ideals of revolution or the assassination of despotic rulers. The 5th of November was a day in which you affirmed your loyalty to the Crown (the celebrations were made compulsory by the government), and though the practice has mostly died out today it was once customary to burn an effigy of Fawkes. Even further forgotten is the fact that for most of their existence, the celebrations on this night routinely turned into anti-Catholic pogroms, with angry drunken mobs attacking Catholic homes and churches, destroying property and singing songs about murdering the Pope.

Icons and ideals

Despite all this historical party-pooping, in the context of the time the Gunpowder Plot was clearly a response to legitimate grievances. While Guy Fawkes would certainly not fit in well on your average modern protest march, and would struggle to relate to the demands of internet pirates, the act of attempting to overthrow an unjust system is something a huge number of people can relate to. Blowing up the Beehive may not be on the cards in the immediate future, but perhaps we can learn something from the determination Fawkes felt to change the world? At the end of the day, the story is a fascinating example of how icons and images can be handed down through the ages, and in the process their meaning can radically change.

This article began with a short verse that has become linked in our heads with revolt and defiance. Guess how the ditty ends?

Guy Fawkes, Guy Fawkes, t’was his intent

To blow up the King and Parli’ment.

Three-score barrels of powder below

To prove old England’s overthrow;

By God’s mercy he was catch’d

With a dark lantern and burning match.

Holla boys, Holla boys, let the bells ring.

Holla boys, holla boys, God save the King!

And what should we do with him? Burn him!