Last week’s decision by the New Zealand police not to press charges against the so-called “Roast Busters” confirmed for many that the police are incapable of taking rape or sexual violence seriously.

For survivors, the close to one-yearlong investigation Operation Clover was a slap in the face. The whole thing seemed faulty even before the investigation began. Despite videos of young men boasting online for having what amounted to non-consensual sex – rape – police initially said that their hands were tied because no one was “brave enough” to come forward to lay a formal complaint. It was revealed days later that someone had laid a formal complaint with the police … two years previously.

Compare this inaction to the police’s proactive stance when it comes to author Nicky Hager. After the publication of Dirty Politics in August revealing the sordid relationship between the National party, rightwing blogger Cameron Slater, lobby groups, and big business, police were knocking on Hager’s door with a search warrant by October.

It seems that the police’s attitude is that rape survivors can wait for three years for justice but a leftwing journalist who uncovers corruption that implicates the Prime Minister and other Ministers at the highest level must be investigated immediately.

While stressing that their main concern was for the “welfare and privacy” of the survivors, Head of Operation Clover Detective Inspector Karyn Malthus went on to outline her concerns that seemed to indicate anything but.

Her first concern was that it is difficult for survivors to come forward under the current system. This is nothing new. We already know that sexual violence and assault is massively underreported and the court process brutalizes and humiliates survivors. As one survivor put it: “The court process for victims of sexual assault is easily the most traumatic thing possible for someone who is already traumatised.”

Malthus’s additional concern of alcohol consumption seems to emphasize exactly why women don’t bother going to the police. She told media that “[t]he prevalence of alcohol in the lives of the teenagers interviewed, both male and female, was a concern.” This is just another way of victim blaming.

To add injury to insult, she goes on to link alcohol consumption to “a poor understanding amongst the males and females spoken to as to what ‘consent’ was … there was an equally poor understanding by these teenagers as to the role alcohol consumption played in potentially negating the ability to consent.”

The assumption Malthus makes is that rape and consent were hard to identify and murky especially given the “shocking” levels of alcohol.

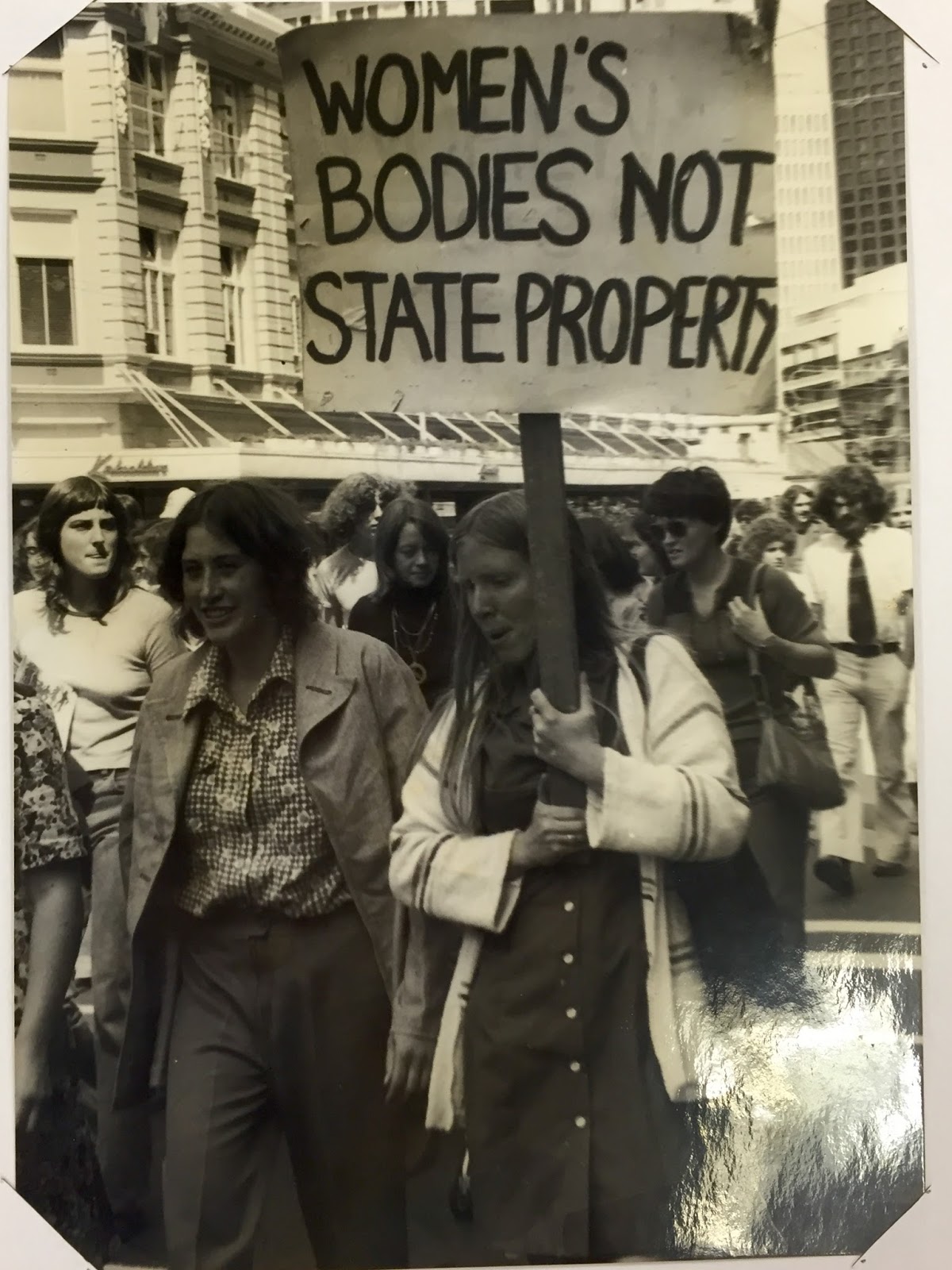

This is a far cry from the slogans raised by the women’s liberation movement that defined consent simply as: ‘yes means yes and no means no’.

The focus on alcohol consumption and ‘poor understanding’ leads to another problem: victim-blaming. It validates the assailant’s experience rather than the survivors. The rights and feelings of the men accused of rape are elevated above the needs of the rape survivor. This was certainly the way ‘Roast buster’ Beraiah Hales’ sister interpreted it when she said that, “They [the police] have done their jobs and proving his innocence has proved that to me.”

It also reduces the assailant’s problem to one of alcohol consumption rather than focusing on the wider issue of sexism in our society. The sick actions of the ‘Roast Busters’ stem from the sick way society allows women to be viewed as sexual objects for men’s pleasure.

People should be angry and appalled at the way police have mishandled the “Roast busters” case. But demanding the police to prosecute or changing the process so that it leads to more prosecutions can be a slippery slope.

It’s clear that police and the justice system have no problems chasing a conviction when the ‘assailant’ is Maori. United Nations Working Party found that New Zealand’s justice system is institutionally racist. The police are not an institution that can be changed into a progressive force.

The incarceration of Teina Pora is a case in point. Pora has spent unjustly 21 years behind bars for the rape and murder of a woman that even the Police Association do not think he committed. He was put behind bars based on a forced confession when Pora was just 17-years-old. Now released on life parole, he has taken his case to the Privy Council in London in an attempt to clear his name.

We need to unequivocally stand with the survivors. Women are in no way to blame for sexual assault, and that sex without consent is rape. But we also must challenge and eradicate the rampant sexism that permeates our entire society. Reforming or strengthening the police or the racist justice system will not help with this.