The forecast was for rain and snow but but the sun shone through for Dunedin’s SlutWalk 2013. About 200 people turned up to oppose victim-blaming, with a hardy few showing some skin to the chilly wind to protest the idea that “slutty clothing” has anything to do with sexual violence.

SlutWalk started in 2010 in a spontaneous, worldwide, outpouring of anger at the comments of a Canadian cop who told a group of women students the way to avoid being raped was not to dress like a slut. In Dunedin, the march was organised by Rape Crisis, whose volunteers help people deal with the aftermath of sexual violence.

Protestors gathered outside the Dental School, before a pretty brisk march up George St to the Octagon. The crowd was mostly, but not exclusively young.

One Rape Crisis volunteer, Su Muse, said she came because she strongly believed victim-blaming was destructive and counter-productive.

“Even here, just before the protest, someone came up and argued it [rape] was about the dress … even on the very day of this protest they had the nerve to do that.”

“What breaks my heart is when this attitude is internalised, when survivors believe that they were to blame.”

Su wears a headscarf. I asked her how she felt about bans on the hijab in Western countries, such as in France.

“It’s just a piece of cloth and if I want to wear it, I am going to wear it … It’s just Islamophobia, especially from France which sees itself as progressive”

But “modest” attire was no protection against rape, she said, as sexual violence in Somalia, where she comes from, showed.

In the Octagon, the rally heard from the national co-ordinator of Rape Crisis, Georgia Knowles, Rebecca Stringer, a gender studies lecturer who has studied the politics of victimhood, and Ken Clearwater, of the Male Survivors of Sexual Abuse group.

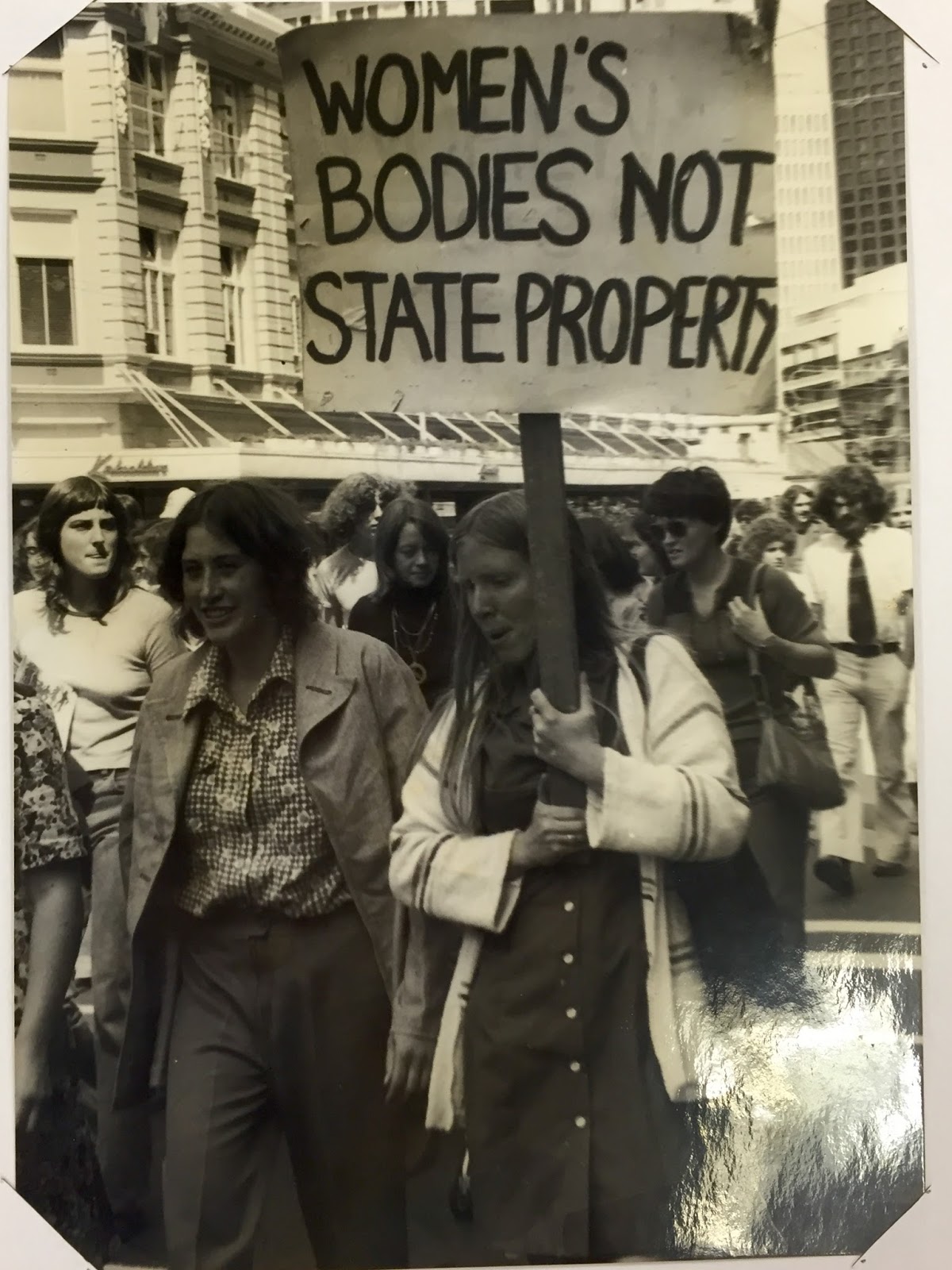

Georgia started by acknowledging the struggle of women in the past, and the victories that had been won. She outlined the origins of the movement. SlutWalk was a global phenomenon and in ever city it had a different kaupapa, she said. In Dunedin, it was organised by Rape Crisis who saw SlutWalk as about reclaiming the word slut in the original, Latin, meaning of reclaim, reclamare, to cry out against. The march was about crying out against the use of the word slut to police women and justify sexual violence. The word slut contributed to a culture of victim-blaming, she said. It policed the victims of assault, judging them for “the way she dresses; the way she walks; the way she talks; the way she sits; the ways she stands; she was out after dark; she invited a man into her house; she said hello to a male neighbour; she opened the door; she looked at a man; a man asked her what time it was and she told him; she sat on her father’s lap; she got into a car with a man; she got into a car with her best friends father or her uncle or her teacher; she flirted; she got married; she had sex once with a man and then said no the next time; she is not a virgin; she talks with men; she talks with her father; she went to a movie alone; she took a walk alone; she went shopping alone; she smiled; she is home alone; she is asleep… And so it goes on.”

Rape was about alienation, power and control, she said. We should choose to love, to make connections, to be courageous.

Georgia said some people were uncomfortable with the word slut and that slutwalk was controversial. There was more than one pathway to fighting sexual violence, she said. The key thing was having the courage to imagine a world without sexual violence, a world of freedom.

Rebecca Stringer thanked Rape Crisis for their work, to applause from the crowd.

“We are here for this demonstration, but Rape Crisis Dunedin is day in, day out, week in, week out, month in, month out, year in, year out, supporting women who have experienced sexual violence,” she said.

The comment of the cop that started the movement was still the major view, she said. SlutWalk presses against that prevailing logic.

“We are forced to point out the obvious, we have to. Like No means No, Clothing is not consent. Clothes don’t rape, it’s a dress not a yes.”

The best thing about the day was that it offered a glimpse of another world, she said.

“A rape-free world is possible. An ethical sexuality is possible,” Rebecca said.

Ken Clearwater opened with the well known saying “He aha te mea nui o te ao?

He tangata! He tangata! He tangata!”

He made two key points. First, thanking Rape Crisis Dunedin for supporting him in his work. In the past Women’s Refuge and Rape Crisis had looked askance at men’s support groups, but that had changed, and he was especially grateful to Rape Crisis Dunedin for leading the way on that. He was grateful too to the women’s lib movement which had won so many gains – “we are able to ride on the skirt tails of strong women”.

His second point was to emphasise that rape was not about sex, or dress, it was about power and control. Ken was himself raped as a 12-year-old, and he was not wearing a minis-skirt, he said. He had recently working with male survivors of rape, by soldiers, in Uganda. Those rapes were about domination, not clothing, he said. And those survivors were having to carry a burden of shame and guilt that did not belong to them. It belonged to the perpetrators, he said.