BOOK REVIEW: Jared Davidson, Sewing Freedom: Philip Josephs, Transnationalism and Early New Zealand Anarchism (AK Press, 2013)

We first encounter Philip Josephs, subject of Jared Davidson’s engrossing, lovingly-written, richly detailed and passionately political new book Sewing Freedom, as he addresses Wellington’s 1906 May Day demonstration: “This meeting sends its fraternal greetings to our comrades engaged in the universal class war, and pledges itself to work for the abolition of the capitalistic system and the substitution in New Zealand of a co-operative commonwealth, founded on the collective ownership of the land and the means of production and distribution.” This motion, for Davidson, captures the essence of Joseph’s anarchism – it was based in “internationalism, class struggle, and free communism.”

Sewing Freedom is a wonderful book, and deserves a wide readership. Davidson, an archivist and anarchist activist, enriches our sense of the political contests and working-class radicalism of the first decades of the twentieth century, and makes a strong case for class-struggle anarchism’s under-appreciated status as an ideological current running through the New Zealand Socialist Party and trade union movements. Josephs, a Jewish migrant from Latvia via a stint in Glasgow, may well have been Aotearoa’s first anarchist. His world, and the thought world of his comrades, allies and enemies in Wellington’s burgeoning workers’ movement, comes alive in this lively, accessible and scholarly book.

Class-struggle anarchism’s part in the history of working-class radicalism has been ill served, Davidson argues, by the narrowly national and theoretically unimaginative frame of most mainstream and social-democratic historiography. That radical ideas – syndicalist, anarchist, socialist, libertarian – circulated in workers’ communities in the years around the great strike of 1913 is without doubt, but many histories of the time down-play these ideas’ influence and hold. A national framework limits any real sense of how ideas travel, Davidson suggests. We should see anarchism instead, he argues, as a “transnational movement”:

“a transnational lens allows New Zealand anarchists to be viewed as part of a wider, international movement, spurred on by transoceanic migration, doctrinal diffusion, financial flows, transmissions of information and symbolic practices, and acts of solidarity. The role of New Zealand anarchism, both in the New Zealand labour movement and its own international movement, increases in scope when placed in such a context.”

Sewing Freedom provides that context. It’s daunting to consider the hundreds of hours of work that must have gone into this book – what makes for engaging reading must have involved some often tedious research, as Davidson makes the best use of limited sources, hostile newspaper reports, radical journals and adverts.

The world he recreates is one that ought to give us a greater sense of the scope and possibility of our radical traditions. Josephs, working as a tailor in Taranaki Street and based for a while in Aro Street, used his tailor’s store as a centre-point for revolutionary ideas and debates; one of his advertisements, reproduced in Sewing Freedom, rather sweetly manages to proclaim both “Workers of all countries unite” and “Fit and latest styles guaranteed.” Josephs imported and distributed, systematically and for the first time, writings by Kropotkin, Bakunin, Emma Goldman, the IWW and others.

He found a ready audience. The densely-populated working-class suburbs of Te Aro and the Aro Valley were, in the early years of the twentieth century, centres of radical thought and organization. The Wellington branch of the New Zealand Socialist Party had nearly 100 members, and 3 000 nationally by the end of the decade. A culture emerged around the Party:

“The NZSP had a significant hand in creating and fostering Wellington’s working-class counter-culture. Political and cultural events, their own newspaper, the Commonweal, and Socialist Hall gave the socialists a presence in the city well beyond their membership – a presence in which Josephs and his anarchism played a major part.”

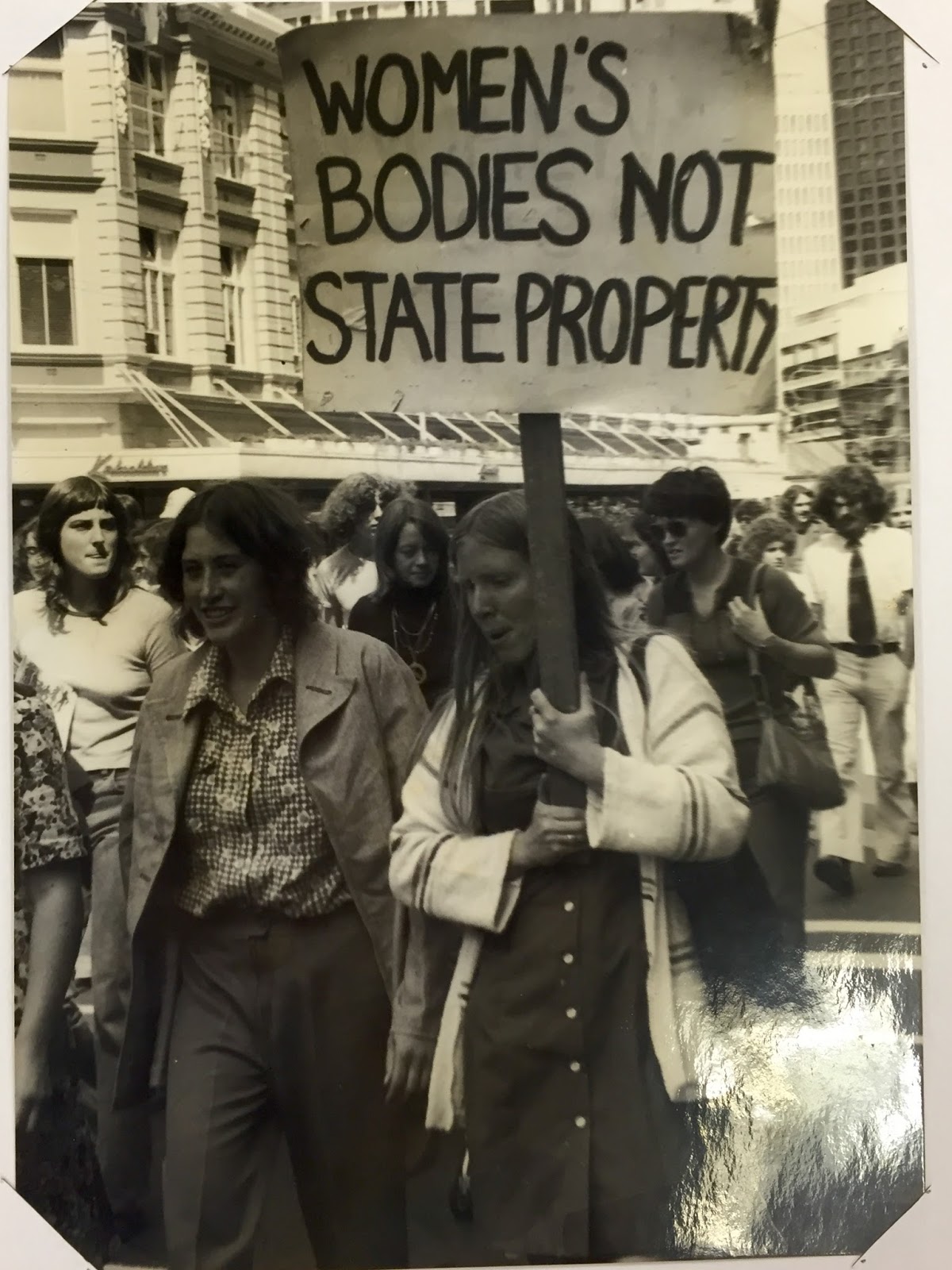

Into this milieu Josephs brought anarchist communism’s stress on the general strike, writing articles for the Maoriland Worker on the general strike as a weapon against conscription, for industrial unionism and class consciousness.

This is, in one sense, sobering reading: a century on, and this radical Wellington, class-conscious, internationalist, political and theoretically engaged, is further from us than it was for our ancestors. Josephs spoke at meetings in support of the 1905 Russian Revolution; joined study circles meeting in the Socialist Hall; agitated and organized, gaining the attention, and repression, of state forces along the way. If it is a world we have lost, however, it is also one we can recreate.

(The prominence of Jewish workers and Jewish intellectual traditions to this internationalist radical network is something else Davidson’s book reminds us of; the sheer scale of the loss and destruction in the Nazi Judeocide makes itself felt in ghostly histories of what might have been, as a whole vibrant and lively world of Eastern European dissent was all but wiped out).

Sewing Freedom’s successes will be apparent to any engaged reader, and do not need further elaboration from me here: buy a copy and find out for yourself, then buy another copy for a friend. I want to end with two criticisms, offered in the generous spirit of the book itself.

The first is to do with labels. Davidson is cross with liberal historians for their borrowing, under-examined, scare-mongering labels for anarchism from press coverage. Quite rightly; there’s more to the tradition than bomb throwing and the propaganda of the deed, and Davidson’s stress on anarchist strands as “part of the wider labour movement” is salutary. Indeed, most of the time his term “anarchist communism” and our own revolutionary socialism seem interchangeable. But, in restoring his political ancestor’s ideological seriousness, I think Davidson sometimes tucks away a few too many stray ends. There is a much messier, more incomplete, political contested story here that stays untold, one of ideas, labels and allegiances in movement and clarification. Josephs stocked George Bernard Shaw (no libertarian!), the US Marxist Daniel De Leon and the Socialist League’s William Morris, another dissident Marxist, alongside Kropotkin and Bakunin. That is no coherent pantheon or apostolic succession; ideas were in flux. Fixing an image of “anarchist communism” too neatly in place obscures that contest.

Secondly, and, for today, more importantly, Sewing Freedom avoids any real assessment of its subject’s political problems or limits. This is perhaps to ask for another book – Davidson’s work is a triumph of historical reconstruction. But the anarchist communists and other radicals in the Socialist Party worked to smash capitalism; their failure, the world we live in today, is our failure. We owe it to them to examine these legacies critically. The great wave of early century revolutionary syndicalism – from the Miners’ Next Step in Britain during the Great Unrest to the Wobblies in the US and Australia, to the National Liberation Federation in Japan – crashed against World War One and the revolutions at its end. Ferocious state repression had a role in this, to be sure, but so did theoretical blind-spots and questions; to do with the state and its role, to do with parties and politics, to do with models of organization. These debates are live ones today; what might we learn, critically, from Philip Josephs as we rediscover him?

How to purchase Sewing Freedom

Sewing Freedom is available at the Freedom Shop on Riddiford Street in Newtown, Wellington and can be ordered through bookstores nationally. You can also buy an e-book version from AK Press direct.