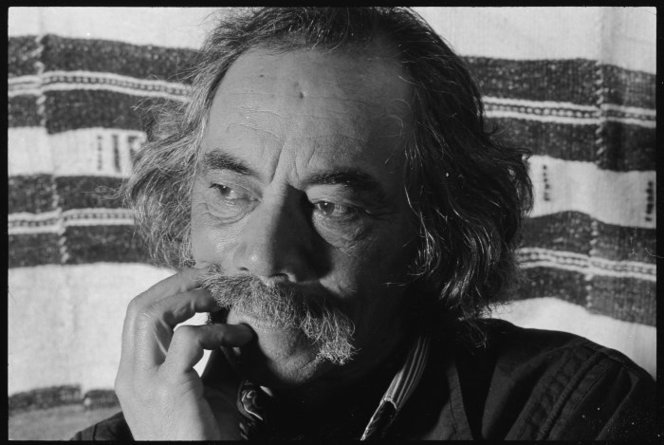

Ralph Hotere – painter, sculptor, collaborator – is a hugely important figure in the art and culture of Aotearoa. His death, as well as being a great and personal loss to his whanau, fellow artists, and community, has historical significance for us all. He was, with his close friend and comrade Hone Tuwhare, one of the leading figures in a generation of engaged artists and intellectuals. One of this country’s greatest painters, Hotere was a rebel, a visionary, and an innovator.

A Maori modernist of fiercely demanding artistic and political drives and ambitions, his work challenges the smug self-images of the day. Hotere’s painting, with its passionate political intensity and bracingly difficult aesthetic challenges, stands as the opposite of all that is praised as ‘middle New Zealand’, the meanness and anti-intellectual banalities that produces a figure as forgettable as John Key. His talents were too obvious, and too enticing, for the establishment to ignore his art; no-one ever succeeded in co-opting Hotere, however. Hotere’s situation was worked out in his own, uncompromising, terms.

Born into a large family in Northland in the early 1930s, Hotere has links and connections with the far north and far south of the country. He worked in and around Dunedin on and off for sixty years, and his iwi, Te Aupōuri, are the people of the northernmost part of Northland. Exposure to the most exciting currents in contemporary European art during trips to London and Europe in the 1960s set a pattern for work and dialogue that stayed constant through his life. Hotere’s work was local without being nationalist; he moved effortlessly between the cosmopolitan and the country, the radical and the rural, bringing the same controlled intensity to each.

Politics, and political commitment, frame Hotere’s work, and his painting is impossible to understand outside of its place as political intervention. Paintings’ titles make this explicit: Black Union Jack from 1981 opposes apartheid in South Africa, and is an intervention into the anti-tour movement of that year; Black Rainbow marks the bombing of Greenpeace’s Rainbow Warrior. A series of paintings and collaborative works responded to threats in the early 1980s from Muldoon’s National government to turn the mudflats around Aramoana near Dunedin into an aluminium smelter. Growing up in Dunedin, these are the works of Hotere’s that have always moved me most affectingly.

All of these works – and anyone who has spent time in bewildered, awed fascination in front of one of Hotere’s intense black paintings will know their power – show just how impoverished, and ideologically motivated, are attempts to separate politics from art. Hotere’s art did not go ‘beyond’ politics but rather drew its energy and daring from this political stance. Painting is not an illustration for a simple ‘message’ with Hotere; it is the message in its own materiality and form. Hotere’s modernism – starkly non-representational , with a strictly worked-out personal style, endless varieties of black – stands apart from the world in which it was produced, and relates to it as a kind of permanent protest.

His is a militant Modernism, and the popularity of these ‘obscure’, demanding, exhilaratingly hard paintings remind us that populist appeals for art to be accessible are usually coded insults directed at ordinary people. Thousands enjoyed and loved Hotere, even while we realised we would never fully ‘understand’ or ‘get’ these elusive works.

That black would become Hotere’s obsession, tool, and object is no purely formal matter, anyway, but is full of political and social significance, and points to some of the ways his works are both local and global. His black and red non-representational paintings draw on the traditions of Maori art and aesthetics, of course, and all of this black – and it is beautiful, glossy, measured – is a visual parallel to the slogans of the 1960s, ‘black is beautiful’ and ‘black power.’

Hotere was inspired by, and remained a militant partisan of, the liberation movements that challenged global capitalism during his youth and early manhood; anti-colonial struggles, the Black struggle in the United States, the movements of the Third World back when this term indicated a project of liberation and not an object of pity, and, centrally, the Maori struggle for self-determination. Hotere identified with workers, the poor and the oppressed. He wore Che Guevera badges and T-Shirts and invested them with political meaning, identifying with the national liberation struggle of the Cuban Revolution long before Che’s image was commodified out of all real existence. Like Hone Tuwhare, Hotere drew great personal and political sustenance from revolutions against the old colonial order and white rule, identifying with the Chinese revolution.

His solidarities were closer to home, too; in a tribute posted on Facebook the day his death was announced, the Maritime Union of New Zealand remember Hotere attending watersiders’ pickets in Port Chalmers as they battled casualisation on the wharves. He was a generous producer and donator of artworks for particular causes and events.

Hotere’s art can be difficult, austere and demanding – wonderfully so, an intellectually astrigent rejoinder to a commodified world in which every aesthetic work is reduced to a readily-consumable marketing item. But it can be witty and playful, too, like White Drip to Mr Paul Holmes, a response to Holmes’ racist rant at the start of the Iraq War or (my favourite) a comment on school discipline in the form of a chair painted black with nails jutting out of its seat.

There will not be any more works from Hotere, but these works that already exist will continue to provoke, challenge, and delight. Just how they manage this combination is best explained by the most fitting tribute Hotere has received, a poem called ‘Hotere’ written decades ago by Tuwhare:

When you stack horizontal lines

into vertical columns which appear

to advance, recede, shimmer and wave

like exploding packs of cards

I merely grunt and say: well, if it

is not a famine, it’s a feast

I have to roll another smoke, man

But when you score a superb orange

circle on a purple thought-base

I shake my head and say: hell, what

is this thing called aroha

Like, I’m euchred, man. I’m eclipsed?

Image credit: ‘Ralph Hotere’. Quinn, Kenneth : Portraits of prominent New Zealanders. Ref: 35mm-27478-23A-F. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. http://natlib.govt.nz/records/23200288