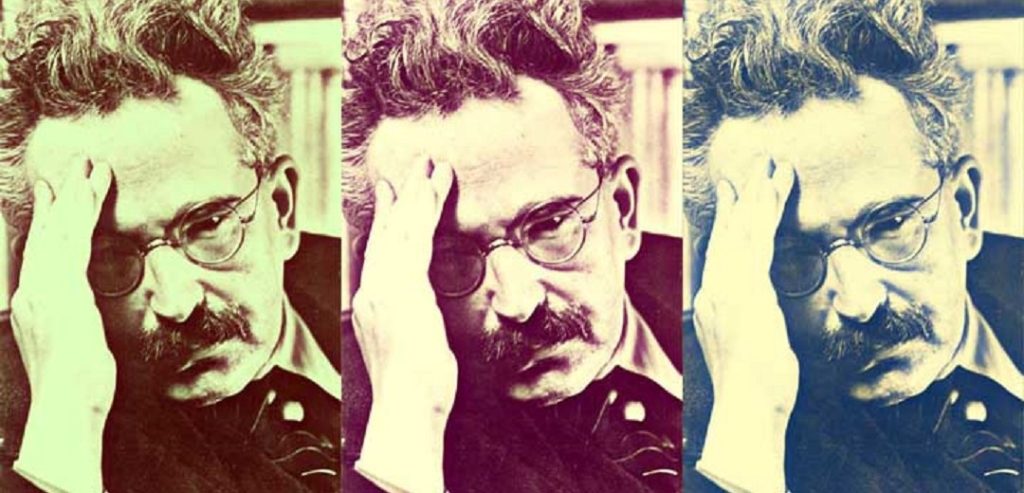

Walter Benjamin was a German-Jewish writer who was born in Berlin in 1892 to a wealthy family with a background in banking and antiques trading. In 1912 he enrolled at university where he studied philosophy and developed a lifelong interest in Romantic literature and poetry. It was also at university that Benjamin first encountered the ideology of Zionism; a feature of Jewish political life that he had been sheltered from by his liberal upbringing. Benjamin arrived at a position which valued and promoted the spiritual depth and cultural value of Judaism whilst rejecting Zionist politics. His commitment to the reality of spiritual Judaism would remain a central feature through his life and writing. Then, in 1924, Benjamin made two discoveries that profoundly affected his philosophical and political thought. The discovery of Lukács’s History and Class Consciousness (1923) and his introduction to Bolshevism via the Latvian theatre director and Bolshevik Asja Lācis, led him to place Communism and later historical materialism at the centre of his thought.

As a writer, Benjamin is entirely unique. His body of work ranges across art criticism, historical investigation, political theory, children’s radio, literary reviews, philosophy and theology. The intellectual standpoint from which he approaches these myriad subjects is an entirely original philosophical position that draws on German Romanticism, Jewish messianism and Marxism; with each perspective folding and feeding into the other. And the style in which he writes is experimental, baroque and often highly cryptic; with sentences that do not always progress into one another and fragmentary essays which offer little in the way of an obvious line of meaning. From this unique position Benjamin engaged with the powerful transformations taking place in 1920s and 30s Europe. He examined the effects of new technologies of mass reproduction, such as film, television and photography, on the public consumption of art. He translated the French poet Beaudelaire into German, took seriously the revolutionary poetics of the Surrealists and, in particular, he turned his attention to the communal ways of life being lost as rapid industrialisation and capitalist development installed a new, alienated routine in the towns and factories of Germany. Benjamin describes, through the 1920s, the degradation of experience that ‘manifests itself in the standardized, denatured life of the civilized masses,’ and ‘in the inhospitable, blinding [experience] of the age of large-scale industrialism’—in particular the life of the unskilled workers whose labour ‘has been sealed off from experience’, degraded, standardised, regimented and reduced to an automaton by modern machinery.

Running through Benjamin’s entire body of work is a struggle against the ideology of progress underpinning bourgeois society. Benjamin saw clearly the threats posed by uninterrupted capitalist progress, namely: the hyper-rationalisation and technicality of war; mankind’s increasing domination of, and alienation from, nature; and the oncoming nightmare of Fascism. In his final work, Theses on the Philosophy of History (1940), completed during the onset of World War II, Benjamin writes, ‘The tradition of the oppressed teaches us that the ‘state of emergency’ in which we live is not the exception but the rule. We must attain a conception of history that accords with this insight.’ For Benjamin, the emergence of Fascism could be understood in two diametrically opposed ways. On the one hand, for the liberal ‘progressive’ doctrine, which sees historical progress, the development of societies towards more democracy, freedom or peace as the norm, Fascism is an exception to the rule, an inexplicable ‘regression’, a parenthesis in the march of humanity. On the other hand, from the standpoint of the oppressed, Fascism is the most recent and brutal expression of the ‘permanent state of emergency’ that is the history of class oppression. Benjamin’s insight was a critique not only of crisis-ridden bourgeois society but of Social Democracy which failed to predict the threat of Fascism because they were bound to the illusion that scientific, industrial and technical progress was incompatible with social and political barbarism.

For Benjamin, revolution was to be the interruption and stilling of the storm of progress, the prevention of new and ever-greater catastrophes, the pulling of the ‘emergency brake’ by the passengers on board a train headed for disaster. Benjamin’s words, published in 1940, ring with a prophetic quality in the wake of the Holocaust, Hiroshima, Vietnam, Iraq, and Syria. And what could describe the present reality of climate change better than as a “permanent state of emergency”? Benjamin saw revolution, then, as the means by which the world can be healed and returned to a state of wholeness; a vision built out of cabbalistic mysticism, an anthropological and Romantic interest in primitive communism and a faith in the revolutionary politics of the working class. Ultimately, Benjamin’s life was cut short by the very forces which he dedicated his life to stopping. Following a failed attempt to cross the border from France to Spain, and fearing being handed over to the German army, Benjamin ended his life on 26 September 1940 at Portbou on the Franco-Spanish border.