I might state that the museum up on the hill known as Parliament House has little attraction for me but if that machine can be used to benefit the working man and foster industrial organisation, I am in favour of it.

W E Parry, January 1913,President of the Waihi Worker’s Union 1909-1912, Minister of Internal Affairs 1935-1949

The party named the New Zealand Labour Party came into being at a meeting on 7 July 1916. This event was little more than a name change of the Social Democratic Party, whose annual conference began the day before. In May the SDP National Executive had recommended the change and to invite the right-wing remnants in the Labour Representation Committees, who had hitherto remained outside the SDP, to join. Eleven out of thirteen of the first Labour Party Executive, and the top officers, were SDP members. The Labour Party formally came into being in 1916, but its real political origins, as the SDP, go back to events of 1912 and 1913.

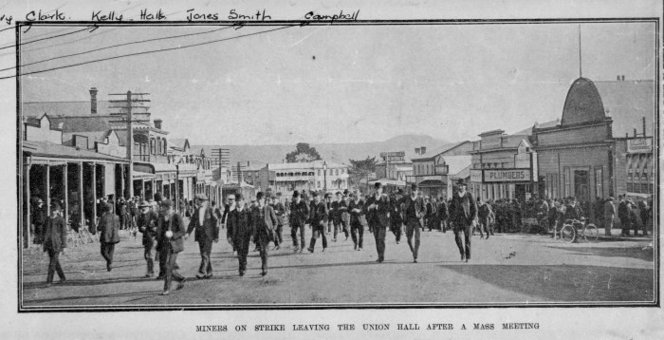

In fact, the origins of the SDP/Labour Party lie precisely in one event, the defeat of the Waihi Strike at the end of 1912. The party was the child of defeat. The SDP was formed in the aftermath of the Waihi Strike as both the political expression of retreat from militancy and unity between left and right wings of the movement, reeling at that time from the shock of state violence used against workers. Up to that time the avowedly revolutionary New Zealand Socialist Party animated the core, industrial sections of the working class, which were organised in unions affiliated to the Federation of Labour.

The SP had been formed in 1901. In 1908 its members led the victorious Blackball Strike, on the strength of which the socialists were able to form the Federation of Miners that year. In 1909 the federation was broadened to become the Federation of Labour, intimately connected to the SP and to be known as the ‘Red Fed’.

The reformist right wing of the labour movement originated in the Trades and Labour Council’s, which were local organisations of mainly small, local craft unions. The TLC’s were pro-Liberal until the Independent Political Labour League was inaugurated in 1905. The League became the New Zealand Labour Party in 1910, which changed its name United Labour Party in 1912.

Former SP members, not least the most revolutionary, Harry Holland, led the SDP from 1913 to 1916, and the Labour Party onwards; but this continuity in personnel does not apply to their politics. After the state smashed of the Waihi Strike, the erstwhile revolutionaries, in reality militant syndicalists, concluded that change, in particular change to the Arbitration Act that was at the heart of the Waihi dispute, must come through political action to bring down the reactionary Massey government. Adopting this new tack, the leaders of the SP and the Red Fed appealed for unity with the reformist wing of the labour movement, represented by the ULP and their union allies in the local TLC’s. The reformist wing of the movement had attacked the long-running Waihi Strike throughout and were whom the SP had been at loggerheads for years. One month before the strike the SP had rejected unity as it was not prepared to drop the Marxist conception of the class struggle and international socialism. Within weeks of the strike’s end the first unity conference took place in January 1913. This was followed by a large conference in July 1913 to create the SDP and the United Federation of Labour. Only a right-wing remnant of the United Labour Party stayed out; it was this grouping that was brought into the fold at the name-changing conference in 1916.

The crushing of the Waihi miners did not quell working class unrest. In October 1913 an employer-provoked miner’s strike at Huntly and a waterfront strike at Wellington was joined by other workers to become the Great Strike. The recently-formed UFL did not want or lead confrontation, but had it thrust upon them by a government and employers who saw their opportunity for a showdown with the working class. Its parties may have united, but the working class was now politically beheaded with no revolutionary party to counter the capitalist class offensive, Massey’s Cossacks and British warships and all, by deepening and broadening the struggle to one aimed at overthrowing the government. After two months of struggle, the Great Strike was defeated.

Defeat upon defeat, unions smashed, more anti-union legislation, and disarray of the SDP; this was the situation as inter-imperialist war started in 1914. In the election that year only two SDP members were elected to Parliament.

Although the right supported Britain’s part and the left were against it, the First World War did not bust the SDP apart. Bruce Brown has explained the oddity:

Had Labour won political power in New Zealand as early as in Australia, the New Zealand movement too would almost certainly have been as sharply divided on the question. But Labour was not in office in New Zealand, even to the extent of controlling a local body of any consequence, On the contrary, it was, or felt itself to be, very much on the wrong end of measures taken by a government representing other and antagonistic interests. Differences of view between moderates and militants then fell to the background as Labour leaders focused on their common and more immediate interests.

Common ground was found over opposition to compulsory conscription, but that was not the defining issue of the age. The truth is that the left, while anti-war, did not break with the pro-war right to form an internationalist party. The failure to break with the rightists was the failure to adopt the perspective of building a revolutionary party to struggle against British imperialism and to champion Māori, women and all the oppressed. This failure to break with reformism cannot be regarded as surprising given that as recently as 1913 the left had buried revolutionary socialism along with the SP.

The Labour Party was born with a leading staff of former revolutionary socialists that gave the newly-named party a left-wing aura. But the socialists did not capture the Labour Party; the party captured, or entrapped, them. Whilst in many countries the war and the Bolshevik Revolution opened a chasm between revolutionaries and reformists, in Aotearoa there would be no alternative party of any weight to affiliate to the Communist Third International. The seeds had been sown in 1912-1913 for a reformist hegemony over the working class. Labour was born of defeat and despair.